Plata Villa - The Christmas Lottery

1952 The town of La Linea had for many years been known throughout the region as La Piojera. By now, however, the name had fallen into disuse in Gibraltar. The Linenses themselves, however, were known by the equally insulting name of Los Rabuos. In fact the name was more of a joke than an insult, as it was meant to differentiate the people of La Linea from the 'tail-less' people of the Rock. The term could be used jokingly or abusively, depending on the intention of the user, and regardless of the fact that by implication a Gibraltarian would be referring to himself as a Barbary ape.

The inhabitants of Gibraltar on the other hand, were known locally as Yanitos or Yanis. The term is derived from the common Italian Christian name of Giovanni or Gianni for short. At that time, however, many of the younger generation of Gibraltarians thought that it was derived from the Spanish corruption of the common English name of 'Johnny'.

The term La Piojera, however, persisted in Spain itself and whenever the football teams of Balonpedica Linense and Algeciras met in third division soccer matches, the fans of the Algeciras team would always make it a point to come armed with insecticide sprays. The insult was usually answered with a particularly inane war cry from the local team,

'Jota, jota, jota, jo . . . jo.

Jota, jota, jota, jo . . . jo.

La Balona, la Balona,

Y nadie mas. '

As a sort of counterpoint to this the people of Algeciras were often ironically referred to as Los Especiales. Referees, of course, were detested regardless of town of origin. In Gibraltar for example, there was a curious expression often used by crowds who were incensed by some particularly inept decision. '¡La gallina!' It harked back to a somewhat bizarre incident which had occurred in pre-war days. An angry spectator had rushed on to the pitch and hit the ref on the head with a chicken.

1952 The town of La Linea had for many years been known throughout the region as La Piojera. By now, however, the name had fallen into disuse in Gibraltar. The Linenses themselves, however, were known by the equally insulting name of Los Rabuos. In fact the name was more of a joke than an insult, as it was meant to differentiate the people of La Linea from the 'tail-less' people of the Rock. The term could be used jokingly or abusively, depending on the intention of the user, and regardless of the fact that by implication a Gibraltarian would be referring to himself as a Barbary ape.

The inhabitants of Gibraltar on the other hand, were known locally as Yanitos or Yanis. The term is derived from the common Italian Christian name of Giovanni or Gianni for short. At that time, however, many of the younger generation of Gibraltarians thought that it was derived from the Spanish corruption of the common English name of 'Johnny'.

The term La Piojera, however, persisted in Spain itself and whenever the football teams of Balonpedica Linense and Algeciras met in third division soccer matches, the fans of the Algeciras team would always make it a point to come armed with insecticide sprays. The insult was usually answered with a particularly inane war cry from the local team,

'Jota, jota, jota, jo . . . jo.

Jota, jota, jota, jo . . . jo.

La Balona, la Balona,

Y nadie mas. '

As a sort of counterpoint to this the people of Algeciras were often ironically referred to as Los Especiales. Referees, of course, were detested regardless of town of origin. In Gibraltar for example, there was a curious expression often used by crowds who were incensed by some particularly inept decision. '¡La gallina!' It harked back to a somewhat bizarre incident which had occurred in pre-war days. An angry spectator had rushed on to the pitch and hit the ref on the head with a chicken.

Badge of the Football Club of La Linea and the Flag of Algeciras Football Club

1953 That year I started smoking seriously. During the month of April I took to locking myself up in my room for hours on end. The pretext was an urgent need for peace and quiet while I revised for my GCE exams. It was a wonderful excuse for having a few quiet fags without being disturbed. My room, however, was quite a small one and despite the precaution of blowing the smoke out of an open window, it soon became pretty evident to everybody that I was smoking. After a few weeks of this absurd state of affairs I confessed to my mother, who much to my surprise, suggested that I was now old enough to smoke openly if I so wished.

My previously surreptitious pilfering of cigarettes from both my brother and sister immediately switched to persistent cadging. At the time Eric and Baba smoked two very different brands of cigarettes. Eric's preference was for Raleigh. They were made from a dark, rather harsh tobacco and came in what were then thought of as an American style pack. It was considered quite macho to smoke them. Baba, on the other hand, was given to buying du Maurier: nothing very macho about these. They were made of tabaco rubio and came in elegant red cardboard boxes. It meant that they both found it hard to smoke each other's brand. It also meant that the amount of money they spent on cigarettes in any given month depended on which style of tobacco I happened to be addicted to at the time.

My previously surreptitious pilfering of cigarettes from both my brother and sister immediately switched to persistent cadging. At the time Eric and Baba smoked two very different brands of cigarettes. Eric's preference was for Raleigh. They were made from a dark, rather harsh tobacco and came in what were then thought of as an American style pack. It was considered quite macho to smoke them. Baba, on the other hand, was given to buying du Maurier: nothing very macho about these. They were made of tabaco rubio and came in elegant red cardboard boxes. It meant that they both found it hard to smoke each other's brand. It also meant that the amount of money they spent on cigarettes in any given month depended on which style of tobacco I happened to be addicted to at the time.

Advertisements for Raleigh and du Maurier cigarettes. The Raleigh advert is probably a war time relic although the type of cigarette pack shown is the same as that used in 1952. The du Maurier advert is from 1951.

It was probably during the month of May that year that I requested a copy of my birth certificate from the relevant authorities. When I received it, I noticed that my date of birth was given as 1939. I was horrified. I was only 14 years old. Someone had told me, quite wrongly of course, that pupils had to be at least 15 to take their School Certificate exams. When I naively asked my mother whether she might have made a mistake about my actual date of birth, she was understandably indignant. On her instructions I checked with the Registrar and was shown the actual folios. There it was, 29th September 1939, signed and countersigned by Pepe, Lina and God knows how many other witnesses and officials. Eventually common sense prevailed. With an untidy stroke of the pen and a few illegible initials, I officially became one year older.

In October the Spanish Sindicato tried to convene a meeting of all Gibraltarian employers to discuss better pay and shorter working hours. The Government of Gibraltar warned employers to stay away from the meeting called by the Spanish workers. The Union was considered illegal, as were the contracts it was presenting. Furthermore any attempt by the employees to induce an employer to sign was to be considered a criminal offence. Despite the strong legal opposition, the Sindicato was eventually recognised de facto. The Spanish ban on the issue of new passes had given the Sindicato great bargaining power. No longer could dismissed workers be replaced from the mass of unemployed of the Campo unless authorised by them. It was a superbly ironic situation.

The Sindicato was an integral part of the Fascist state machinery and was controlled by the one and only party ever permitted by the Nationalist government, the FET y de las JONS, alias Falange Espanola Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista, without doubt the most clumsily titled political party in history. It was usually referred to as el Movimiento. The sindicates were, of course, vertical in structure, with precious little communication or rapport between appointed union leaders and the grass roots. Even the shop floor stewards were usually appointees. The workers, the majority of whom were not exactly enamoured with the regime, were extremely careful about what they said in his presence.

In October the Spanish Sindicato tried to convene a meeting of all Gibraltarian employers to discuss better pay and shorter working hours. The Government of Gibraltar warned employers to stay away from the meeting called by the Spanish workers. The Union was considered illegal, as were the contracts it was presenting. Furthermore any attempt by the employees to induce an employer to sign was to be considered a criminal offence. Despite the strong legal opposition, the Sindicato was eventually recognised de facto. The Spanish ban on the issue of new passes had given the Sindicato great bargaining power. No longer could dismissed workers be replaced from the mass of unemployed of the Campo unless authorised by them. It was a superbly ironic situation.

The Sindicato was an integral part of the Fascist state machinery and was controlled by the one and only party ever permitted by the Nationalist government, the FET y de las JONS, alias Falange Espanola Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista, without doubt the most clumsily titled political party in history. It was usually referred to as el Movimiento. The sindicates were, of course, vertical in structure, with precious little communication or rapport between appointed union leaders and the grass roots. Even the shop floor stewards were usually appointees. The workers, the majority of whom were not exactly enamoured with the regime, were extremely careful about what they said in his presence.

Flechas y Pelayos, the magazine of the FET y de las Jons.

The top sindicate boss in La Linea was a somewhat sinister gentleman called Sr. Vilche. He was never seen without his sunglasses and was reputed to be quite high up in the party hierarchy. In theory, Sr. Vilche was in a position to order his workers to take strike action in Gibraltar, despite the fact that it was illegal to strike in Spain itself, not to mention the fact that since the FET y de las JONS was part of the state apparatus, it could be interpreted as a political act with all its consequent diplomatic ramifications.

In an ideal world it would have been best if the Spanish workers had been able to join the TGWU in Gibraltar as this would have allowed labour to flex much stronger muscles. Unfortunately it was the time of the Cold War, and the Rock had again become a base of great significance, not just for Britain but for the whole NATO alliance. A really powerful labour movement was just about the last thing the British authorities wanted. Nevertheless, successes by the Spanish Union did help the TGWU and vice versa.

Meanwhile the Government of Gibraltar dropped the trades tax and imposed income tax. It was met with surprisingly little opposition. By international standards it was minute, and in any case, as some people jokingly suggested,

'Hay que pagar algo para los monos'.

In fact Gibraltar seems to have been doing reasonably well economically, and the harbour and dockyard continued to entice large numbers of merchantmen, liners and warships of many different nationalities.The Russian 'Klondykers' called constantly, spending small fortunes on Western goods to take back home. The sailors were always instantly recognisable by their huge baggy trousers and generally ill-fitting clothes.

For many years the ships of the Italia line also called regularly at Gibraltar on their way to or from the USA. These magnificent transatlantic ships could often be seen from any of the eastern beaches of the Rock as they steamed into and out of the Mediterranean. Their wash took a while to reach the shore, but when they did they raised a series of glorious waves, every one a surfer's dream. The stars were the Michaelangelo, the Leonardo da Vinci and the ill-fated Andrea Doria. That summer the latter sank off the coast of the USA a few days after leaving Gibraltar.

In an ideal world it would have been best if the Spanish workers had been able to join the TGWU in Gibraltar as this would have allowed labour to flex much stronger muscles. Unfortunately it was the time of the Cold War, and the Rock had again become a base of great significance, not just for Britain but for the whole NATO alliance. A really powerful labour movement was just about the last thing the British authorities wanted. Nevertheless, successes by the Spanish Union did help the TGWU and vice versa.

Meanwhile the Government of Gibraltar dropped the trades tax and imposed income tax. It was met with surprisingly little opposition. By international standards it was minute, and in any case, as some people jokingly suggested,

'Hay que pagar algo para los monos'.

In fact Gibraltar seems to have been doing reasonably well economically, and the harbour and dockyard continued to entice large numbers of merchantmen, liners and warships of many different nationalities.The Russian 'Klondykers' called constantly, spending small fortunes on Western goods to take back home. The sailors were always instantly recognisable by their huge baggy trousers and generally ill-fitting clothes.

Russian fishing crew buying out the town - This photo was taken in the 1960s by which time the baggy trousers had become a thing of the past.

For many years the ships of the Italia line also called regularly at Gibraltar on their way to or from the USA. These magnificent transatlantic ships could often be seen from any of the eastern beaches of the Rock as they steamed into and out of the Mediterranean. Their wash took a while to reach the shore, but when they did they raised a series of glorious waves, every one a surfer's dream. The stars were the Michaelangelo, the Leonardo da Vinci and the ill-fated Andrea Doria. That summer the latter sank off the coast of the USA a few days after leaving Gibraltar.

Postcard of the Italian transatlantic liner Andrea Dorea.

Italian postcard of the Andrea Doria

Sometimes warships flying enormous streamers called 'Paying out Pennants' put into port on their way to their home bases in Britain. The streamers were a throwback to the days when crews were taken on for a specific journey and then paid off and discharged.

The longer the crew had been away, the longer the pennant. In the modern navy it meant that the ship had finished its tour of duty with a specific fleet. This in turn implied that the vessel was due for a refit and that the crew were soon to be given a period of extended leave. Hence ships flying the pennant always seemed to have an air of celebration about them.

HMS Vanguard, and the USS Missouri or 'Mighty Mo', were also frequent callers. They were the last and largest battleships ever built for the Royal and United States Navies respectively.

HMS Vanguard and the USS Missouri. The last and the largest battleships ever built for the British and US Navy. They were frequent visitors to Gibraltar and I and my brother Eric remember staring up in awe at their towering bows when we were out in the harbour training for some regatta or other. The American ship was always referred to as ‘Mighty Mo’.

Air travel was also on the increase. British European Airways now had a regular service to London via Madrid, and during the summer there were innumerable charter flights with tourists on their way to the Costa del Sol. There was also a regular service to Tangier run by a local company called Gibraltar Airways. For many years they used an old DC3 which was affectionately known to the locals as Yogi Bear. The reason for this absurd nickname was that the plane's registration letters were YO. This meant that the words which appeared on the fuselage read: YO-GIBAIR.

During the month of August, sting rays were known to gather just off the shores of Eastern beach. One day a group of intrepid underwater fishermen, including me, set out to try their luck at harpooning some of these unfortunate beasts. Eventually I managed to spear a tiny specimen. The average size of a sting ray is about a yard across its fins. This one was about the size of a postage stamp.

A newer version of YO-GIBAIR. The original was a DC3 Dakota

During the month of August, sting rays were known to gather just off the shores of Eastern beach. One day a group of intrepid underwater fishermen, including me, set out to try their luck at harpooning some of these unfortunate beasts. Eventually I managed to spear a tiny specimen. The average size of a sting ray is about a yard across its fins. This one was about the size of a postage stamp.

Sting Ray. This is exactly what the fish looked like as it lay on the sandy bottom of Eastern Beach.

Bringing my catch ashore, I was met by a school friend whose name, unbelievably, was Charlie Chan and whose family, quite believably, was originally from Hong Kong. Charlie, who had never seen a ray before, came over to have a closer look. The tiny fish took fright, and lashed out with its tiny tail. The poisonous barb hit a vein in Charlie's wrist and five minutes later he was lying on the sand, writhing about in agony. He spent nearly two weeks in hospital and for a while it seemed certain that his arm would have to be amputated. Ever since then, sting rays were always given a very wide berth.

Nevertheless, I do seem to have been a rather slow learner. Not too long after this event I harpooned quite a large electric ray off Getares beach. Unthinkingly I grabbed hold of the metal spear and recieved a thoroughly nasty shock. The elasmobranch was hastily added to the list of species to be left severely alone.

As I walked home the Saturday before Christmas I was hailed from the window of her house by Lewis Hathaway's sister Laura who asked me whether I had heard that Eric had won the lottery. Replying that I hadn't, I walked on home thinking she had meant that he had won one of the minor prizes. It was only after I had moved on some distance that I realised that Laura would not have known if Eric had won a minor prize; after all these were really quite common. Could it be he had won the third prize? It was only when I opened the door to 42 Alameda House and saw the pale look on my mother's face and the amazement in her eyes that I realized what had happened.

Eric had won £2 500, a 4th share of the first prize of the Gibraltar Christmas Lottery. In those days it was an enormous amount of money. Eric shared some of his winnings as follows:

Maruja £ 100 for a holiday

Grannie A Dunlopilo

A radiator

A cardigan

Some stockings

Neville Trip to Lourdes

A Humber bicycle

A tennis racquet

Eric £100

An Austin 7 car

Nevertheless, I do seem to have been a rather slow learner. Not too long after this event I harpooned quite a large electric ray off Getares beach. Unthinkingly I grabbed hold of the metal spear and recieved a thoroughly nasty shock. The elasmobranch was hastily added to the list of species to be left severely alone.

As I walked home the Saturday before Christmas I was hailed from the window of her house by Lewis Hathaway's sister Laura who asked me whether I had heard that Eric had won the lottery. Replying that I hadn't, I walked on home thinking she had meant that he had won one of the minor prizes. It was only after I had moved on some distance that I realised that Laura would not have known if Eric had won a minor prize; after all these were really quite common. Could it be he had won the third prize? It was only when I opened the door to 42 Alameda House and saw the pale look on my mother's face and the amazement in her eyes that I realized what had happened.

Eric had won £2 500, a 4th share of the first prize of the Gibraltar Christmas Lottery. In those days it was an enormous amount of money. Eric shared some of his winnings as follows:

Maruja £ 100 for a holiday

Grannie A Dunlopilo

A radiator

A cardigan

Some stockings

Neville Trip to Lourdes

A Humber bicycle

A tennis racquet

Eric £100

An Austin 7 car

Modern version of a Gibraltar lottery ticket

It is only in retrospect that one can really appreciate my mother’s constant struggle to make ends meet. That lucky lottery ticket must have seemed to her the answer to all her prayers. Significantly, her note-book entries are in ink, in her clear distinctive handwriting, while all the foregoing litany of measly pay packets and humdrum petty expenses are in pencil.

Despite being broke most of the time, the Chipulina children enjoyed their life with no sense of deprivation whatsoever: the natural optimism of youth, no doubt, but also a tribute to Lina's quietly efficient administration of their scant resources. In doing so she shielded them from the stark realities of their position. As Eric once wrote when commenting on the above,

'Se me saltan las lágrimas cuando lo pienso.'

Baba spent her lottery money on a holiday in the U.K. travelling by P & O. Together with Anchor Line and Orient they still retained a regular service from Gibraltar as in the old days. She stayed with a friend who had married an Englishman and now lived in Richmond. Everyday she set off by bus and tube to explore London with an A to Z street map. She claimed that she had never got lost. She returned with presents for everybody and even brought back some change from her 100 pounds.

My new bicycle, an unusual black Humber, replaced a dangerous heavy old antique which I had had for a while. A year or so previously I had fallen off this monster while travelling back home from school. The hill leading to Plata Villa School was called La Cuesta de los Locos. Prior to going to Plata Villa, I had always thought that the name La Cuesta de los Locos referred to the sheer steepness of the road. In fact it referred to a mental hospital that had once stood at the top of the hill. Its official name was Witham's Road, in honour of Captain Witham of Great Siege fame. Perhaps a more appropriate colloquial name would have been La Cuesta del Loco.

Whatever its history it was extremely steep. For some now long forgotten reason, I had been forced to brake violently at the bottom of the road and had flown over the handle bars. I sprained one of my wrists badly and broke the main frame of the bike. Not being able to afford anything better, I eventually repaired it with a badly fitting brass tube which tended to press against the brake mechanism. This caused the monstrosity to come to a juddering halt at the most inopportune moments.

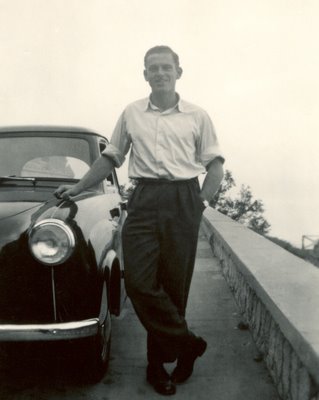

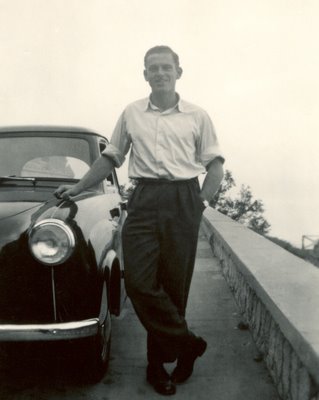

The new Humber was a very welcome replacement. I kept it in the veranda and polished it constantly. Eric's new car was a four door Austin 7, a model which was very popular at the time. It was a small car with a rather odd narrow shape and the company that manufactured it seemed to be in agreement with Henry Ford's dictum concerning his famous Model T. You could buy an Austin in any colour you liked as long as it was black. Its registration number was G 9732 and it was the family's first car.

Despite being broke most of the time, the Chipulina children enjoyed their life with no sense of deprivation whatsoever: the natural optimism of youth, no doubt, but also a tribute to Lina's quietly efficient administration of their scant resources. In doing so she shielded them from the stark realities of their position. As Eric once wrote when commenting on the above,

'Se me saltan las lágrimas cuando lo pienso.'

Baba spent her lottery money on a holiday in the U.K. travelling by P & O. Together with Anchor Line and Orient they still retained a regular service from Gibraltar as in the old days. She stayed with a friend who had married an Englishman and now lived in Richmond. Everyday she set off by bus and tube to explore London with an A to Z street map. She claimed that she had never got lost. She returned with presents for everybody and even brought back some change from her 100 pounds.

My new bicycle, an unusual black Humber, replaced a dangerous heavy old antique which I had had for a while. A year or so previously I had fallen off this monster while travelling back home from school. The hill leading to Plata Villa School was called La Cuesta de los Locos. Prior to going to Plata Villa, I had always thought that the name La Cuesta de los Locos referred to the sheer steepness of the road. In fact it referred to a mental hospital that had once stood at the top of the hill. Its official name was Witham's Road, in honour of Captain Witham of Great Siege fame. Perhaps a more appropriate colloquial name would have been La Cuesta del Loco.

Whatever its history it was extremely steep. For some now long forgotten reason, I had been forced to brake violently at the bottom of the road and had flown over the handle bars. I sprained one of my wrists badly and broke the main frame of the bike. Not being able to afford anything better, I eventually repaired it with a badly fitting brass tube which tended to press against the brake mechanism. This caused the monstrosity to come to a juddering halt at the most inopportune moments.

The new Humber was a very welcome replacement. I kept it in the veranda and polished it constantly. Eric's new car was a four door Austin 7, a model which was very popular at the time. It was a small car with a rather odd narrow shape and the company that manufactured it seemed to be in agreement with Henry Ford's dictum concerning his famous Model T. You could buy an Austin in any colour you liked as long as it was black. Its registration number was G 9732 and it was the family's first car.

Eric and his brand new Austin. Photo was taken on the road to Sandy Bay.

Incidentally at that time British cars were thought to be vastly superior to foreign ones. Whenever an Italian or French car maker came up with a new model the standard test was to press down hard on the bonnet and comment in a loud voice. '¡Esta hecho de lata! British cars of the era were definitely made of thicker steel plate than foreign ones.

Returning to military matters the U.S.A. and Spain signed a bilateral agreement for the construction and joint use of naval military bases at Rota and Cartagena. Meanwhile the Korean War finally came to an inconclusive end when the Armistice was signed at Panmumjom. In the dying days of the conflict a British destroyer called HMS Amethyst had carried out some particularly heroic exploit. On its way home to England for urgent repairs it arrived in Gibraltar with its hull riddled with bullet holes. It received a hero's welcome. A veritable armada of local small craft accompanied the ship into the harbour to the tune of every available siren and foghorn in town.

Also somewhere around this period Ruby Wills married an ex-Army Warrant Officer called Norman Cooper. They left Gibraltar and went to live in Poole, Dorset.

Returning to military matters the U.S.A. and Spain signed a bilateral agreement for the construction and joint use of naval military bases at Rota and Cartagena. Meanwhile the Korean War finally came to an inconclusive end when the Armistice was signed at Panmumjom. In the dying days of the conflict a British destroyer called HMS Amethyst had carried out some particularly heroic exploit. On its way home to England for urgent repairs it arrived in Gibraltar with its hull riddled with bullet holes. It received a hero's welcome. A veritable armada of local small craft accompanied the ship into the harbour to the tune of every available siren and foghorn in town.

Also somewhere around this period Ruby Wills married an ex-Army Warrant Officer called Norman Cooper. They left Gibraltar and went to live in Poole, Dorset.