1908 It is not known for certain why Maria Luisa (2.4) returned to Gibraltar for good, but return she did to her father's house in 42 Crutchett's Ramp. It was probably not quite up to the standards she had become accustomed to in India but she could have done far worse. Despite its rather gloomy entrance, the top flats were bright and spacious.

1908 Main Street, Gibraltar. The archway on the left of the car is the entrance to the Gibraltar Post Office, Telegraph and Savings Bank. One of my great grandfathers, Joseph Chipulina (3.1) had been made Chief Clerk in the Post Office in 1899. His son Angel, who was another of my grandfathers, would also end up having an important position there. So would Joseph’s other sons, José-Angel and Thelmo.

Apart from the view over the bay on the street side, the large windows or cristalera overlooking the patio at the rear caught the sun from the moment it rose above the Rock until mid-afternoon. After that the walls of the buildings behind which were on a higher level, kept on reflecting sunlight until the sunset. Maria Luisa (2.4) and her daughter occupied the recently built third floor flat. The terrace proved a boon during the height of summer when the roof overheated and the house became an oven. On particularly hot days it must have been agony to wait for the sun to have the decency to drop westward so that they could cart their stuff out and settle down to eat, chat or whatever until it was time for bed. It was also very pleasant to have lunch out on the terrace on fine, crisp winter days.

When electricity was finally installed in Crutchett's Ramp, Diego José (3.7) was singularly unimpressed. He thought the light it produced was weak by comparison to the paraffin lamps commonly in use at the time. Maria Luisa's brother apparently resented their presence in the house. The family rented out the first floor flat. Perhaps he felt his father was losing out by not being able to make money on the top one.

The following were some of the items which Maria Luisa (2.4) brought back from Bombay:

When electricity was finally installed in Crutchett's Ramp, Diego José (3.7) was singularly unimpressed. He thought the light it produced was weak by comparison to the paraffin lamps commonly in use at the time. Maria Luisa's brother apparently resented their presence in the house. The family rented out the first floor flat. Perhaps he felt his father was losing out by not being able to make money on the top one.

The following were some of the items which Maria Luisa (2.4) brought back from Bombay:

beautifully carved, wooden, octagonal side table,

wooden tripod with legs carved in the form of animals, supporting an engraved bronze tray,

bamboo bookshelf,

wooden tripod with legs carved in the form of animals, supporting an engraved bronze tray,

bamboo bookshelf,

handful of very small hindu idols,

silver whisky measure,

ornate solid silver tea set,

my mother's notorious phallic lucky charm.

Many of these survived and were in everyday use for many years to come. Except for the phallic lucky charm of course. Among other items which also returned to Gibraltar but were not necessarily of Indian origin was a small solid silver matchbox holder. The initials G.R. are prominently engraved on one side. Who G.R. was is something of a mystery. None of the names of known former colleagues fit these initials. One thing is certain, however. G.R. was not a woman. Otherwise Maria Luisa (2.4) would never have kept the thing. Soon after arrival Lina was sent to the Loreto Convent School.

silver whisky measure,

ornate solid silver tea set,

my mother's notorious phallic lucky charm.

Many of these survived and were in everyday use for many years to come. Except for the phallic lucky charm of course. Among other items which also returned to Gibraltar but were not necessarily of Indian origin was a small solid silver matchbox holder. The initials G.R. are prominently engraved on one side. Who G.R. was is something of a mystery. None of the names of known former colleagues fit these initials. One thing is certain, however. G.R. was not a woman. Otherwise Maria Luisa (2.4) would never have kept the thing. Soon after arrival Lina was sent to the Loreto Convent School.

The Loreto Convent School

Soon after Maria Luisa Letts (2.4) returned to Gibraltar for good, she sent her daughter Lina to the Loreto. As she was not very well off at the time the nuns made a reduction in her school fees. This seems to have been prompted by the fact that her father Diego Gomez (3.7) had always been very generous to the order when Maria Luisa had herself had attended another of their schools. In 1946 I also did some of my primary schooling at the Loreto Convent. As my family were still broke the nuns apparently took me on for free. My grandfather’s past generosity seems to have had a very lasting effect. .

Alfonso and Victoria notwithstanding, Edward VII's private secretary thought it politic to write to General Walker, Governor of Gibraltar, that it would be advisable to change the name of his residence from 'The Convent', a name with Spanish and Roman Catholic connections, to the more British, 'Government House'. The reason given was that during the King's visit, the press had reported his lunch at the Convent. Soon after a Protestant association had deplored the fact that the King had thought it necessary not only to visit, but even to have luncheon, at such a Roman Catholic institution.

Alfonso and Victoria notwithstanding, Edward VII's private secretary thought it politic to write to General Walker, Governor of Gibraltar, that it would be advisable to change the name of his residence from 'The Convent', a name with Spanish and Roman Catholic connections, to the more British, 'Government House'. The reason given was that during the King's visit, the press had reported his lunch at the Convent. Soon after a Protestant association had deplored the fact that the King had thought it necessary not only to visit, but even to have luncheon, at such a Roman Catholic institution.

Contemporary tinted photograph of the ‘Convent’

It was while these crucial discussions were taking place that Maria Luisa's (2.4) sister Anita, married a gentleman called Byrne who also worked for the Eastern Telegraph Company. The couple lived in Camp Bay and Maria Luisa and her daughter Lina often came visiting. The husband had some sort of job as caretaker in charge of the huge tanks that contained the cables at the terminal there. Before Maria Luisa and her daughter were allowed to go down to the Bay, a sentry would call Byrne to verify that they were bona fide visitors.

At the time my father Pepe Chipulina (1.1) was 13 years old and was being educated by the Christian brothers at Line Wall College. There is an anecdote relating to this period concerning a certain lay teacher called Monsieur Busquet, who gave French lessons at the school. He often took to wearing a Galleta type hat which he would leave on the rack while teaching.

One day he found his beloved hat impaled on its hook. He was absolutely furious as he confronted the brothers demanding instant reprisal. One of the brothers tried to appease him.

'¡Son niños, M. Bousquet, 'son niños!'

'¡Niños?' replied the irate Frenchman, '¡estos no son niños, estos son hijos de puta!'

Although in no way related to the above anecdote, the prostitutes of Gibraltar had recently been banished from the Rock and had set up shop in La Calle de Gibraltar in La Linea.

That year the British constructed a steel fence in 'no-man's land.' From now on every evening, the gates were closed with great ceremony. Despite this, relations with Spain were still reasonably friendly. This was advantageous not only to the Gibraltarians but to Spaniards as well. The finest house of the period in Gibraltar for example, was the Aaron Cardozo Regency mansion which belonged to the Spanish Larios family who owned a cork factory in La Linea as well as much of the hinterland.

At the time my father Pepe Chipulina (1.1) was 13 years old and was being educated by the Christian brothers at Line Wall College. There is an anecdote relating to this period concerning a certain lay teacher called Monsieur Busquet, who gave French lessons at the school. He often took to wearing a Galleta type hat which he would leave on the rack while teaching.

One day he found his beloved hat impaled on its hook. He was absolutely furious as he confronted the brothers demanding instant reprisal. One of the brothers tried to appease him.

'¡Son niños, M. Bousquet, 'son niños!'

'¡Niños?' replied the irate Frenchman, '¡estos no son niños, estos son hijos de puta!'

Although in no way related to the above anecdote, the prostitutes of Gibraltar had recently been banished from the Rock and had set up shop in La Calle de Gibraltar in La Linea.

That year the British constructed a steel fence in 'no-man's land.' From now on every evening, the gates were closed with great ceremony. Despite this, relations with Spain were still reasonably friendly. This was advantageous not only to the Gibraltarians but to Spaniards as well. The finest house of the period in Gibraltar for example, was the Aaron Cardozo Regency mansion which belonged to the Spanish Larios family who owned a cork factory in La Linea as well as much of the hinterland.

Aaron Cardozo’s Regency mansion in Commercial Square

General Sir Archibald Hunter. Once known as ‘Our youngest general’ he was also described as “a good soldier but obstinate and not quite normal in his actions when he sees red". As Governor of Gibraltar, his high-handed attitude alienated the civilian inhabitants, and he was recalled prematurely.

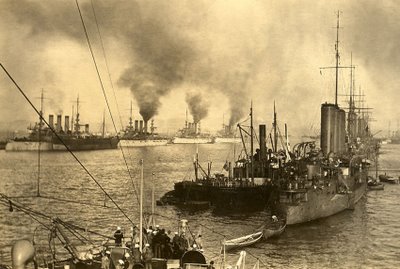

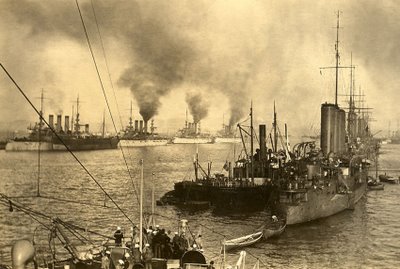

Gibraltar Harbour. The Americans came visiting and there was little space left for anybody else. My father Pepe Chipulina was fourteen years old at the time. The Americans would return in 1917 when the USA made Gibraltar their main Mediterranean naval base.

1909/10 The civilian population now stood at 18 351. General Sir Archibald Hunter became Governor and both the Letts and Gomez families, who were living in 42 Crutchett's Ramp at the time, witnessed the appearance of Halley's Comet from the terrace of their house. Even the heavens had put on a show to welcome Sir Archibald.

General Sir Archibald Hunter. Once known as ‘Our youngest general’ he was also described as “a good soldier but obstinate and not quite normal in his actions when he sees red". As Governor of Gibraltar, his high-handed attitude alienated the civilian inhabitants, and he was recalled prematurely.

Gibraltar Harbour. The Americans came visiting and there was little space left for anybody else. My father Pepe Chipulina was fourteen years old at the time. The Americans would return in 1917 when the USA made Gibraltar their main Mediterranean naval base.

Appropriately, Gibraltar had also just become a Catholic bishopric. That same year Edward VII died, George V was crowned king, and the Rock Apes of the species Macacus inuus, now numbering 200 individuals, split into two packs.

No relation. A Rock Ape

But it was not only the apes that were on the move. The firm Turner & Co. who normally concerned themselves with coal, shipping and general imports, now focussed their resources on the business of emigration. That year some 10 000 emigrants, mainly from Spain, embarked in Gibraltar for Buenos Aires. The third class fare was 175 pesetas.

1911 Very few Gibraltarians, however, seem to have been persuaded to make the move to Argentina. The census showed a civilian population of 19 583, quite a large increase from the previous one. Perhaps they were reluctant to miss the first Gibraltar fair which was held in May the following year at the Grand Parade.

My mother Lina (1.2) was now a very pretty 12 year old. She must have caused something of a stir when she went to the market, as the vendors would often point her out as 'La nieta de Don Diego.' Her grandfather was, of course, well known to them as a fruit wholesaler. The market in those days covered quite a large area. The entrance was dominated by fishmongers. The fish were laid out in heavy stone tables which occupied quite a large proportion of the available space. As Colonel Drinkwater had observed many years previously during the Great Siege, Gibraltar,

'. . . is very rich in fish. The John-Doree, turbot, sole, salmon, hake, rock-cod, mullet, and ranger, with a variety of less note, are caught along the Spanish shore and in different parts of the bay. Mackerel are also taken in vast numbers . . . and shell-fish are brought from neighbouring parts.'

The fruit and vegetable stalls lined a narrow alleyway which led towards other stalls selling just about anything else that was edible. As can also be deduced from the following nonsense rhyme, beef and other types of meat were also on sale in the market.

'Mi madre no quiere, mi madre no quiere

Que vaya a la plaza . . a . . a

Porque el carnicero . . o . . o

Tiene mucha guasa . . a . . a.

Si le pido carne, si le pido carne

Me da una chuleta . . a . . a

Y con la otra mano . . o . . o

Me toca las teta' . . a . . a

Que te tumbo, niña, que te tumbo,

Que te tumbo que te tumbaré,

Y la muy sinverguenza me dice,

No me tumbe que yo me hecharé.'

1911 Very few Gibraltarians, however, seem to have been persuaded to make the move to Argentina. The census showed a civilian population of 19 583, quite a large increase from the previous one. Perhaps they were reluctant to miss the first Gibraltar fair which was held in May the following year at the Grand Parade.

My mother Lina (1.2) was now a very pretty 12 year old. She must have caused something of a stir when she went to the market, as the vendors would often point her out as 'La nieta de Don Diego.' Her grandfather was, of course, well known to them as a fruit wholesaler. The market in those days covered quite a large area. The entrance was dominated by fishmongers. The fish were laid out in heavy stone tables which occupied quite a large proportion of the available space. As Colonel Drinkwater had observed many years previously during the Great Siege, Gibraltar,

'. . . is very rich in fish. The John-Doree, turbot, sole, salmon, hake, rock-cod, mullet, and ranger, with a variety of less note, are caught along the Spanish shore and in different parts of the bay. Mackerel are also taken in vast numbers . . . and shell-fish are brought from neighbouring parts.'

The fruit and vegetable stalls lined a narrow alleyway which led towards other stalls selling just about anything else that was edible. As can also be deduced from the following nonsense rhyme, beef and other types of meat were also on sale in the market.

'Mi madre no quiere, mi madre no quiere

Que vaya a la plaza . . a . . a

Porque el carnicero . . o . . o

Tiene mucha guasa . . a . . a.

Si le pido carne, si le pido carne

Me da una chuleta . . a . . a

Y con la otra mano . . o . . o

Me toca las teta' . . a . . a

Que te tumbo, niña, que te tumbo,

Que te tumbo que te tumbaré,

Y la muy sinverguenza me dice,

No me tumbe que yo me hecharé.'

The old market place.

Although fruit and vegetables came from Spain, livestock was imported from Morocco, as was game poultry and eggs. The cattle were slaughtered at the Matadero in the South end of Eastern Beach. On one much celebrated occasion, a heifer escaped and created havoc in the vicinity. In the town centre, the activities in Commercial Square had by now degenerated into a veritable flea market. The place was known as the 'Jew's Market' by the British but its old associations with auctions persisted, and the locals continued to call it el Martillo.

1912 It was also a period when people could walk about at any hour without fear of being molested by drunken servicemen. Military discipline at the time was strict to the point of harshness. Nevertheless there was one occasion when Maria Luisa (2.4) and young Lina (1.2) were accosted by a drunken soldier. My mother later recalled indignantly that Maria Luisa had fled the scene leaving her alone to face the man, who fortunately was just mawkish drunk and well past violence.

Elsewhere tragedy struck. On the 12th of April, the 46 000 ton White Star liner Titanic struck an iceberg off Newfoundland on her maiden voyage and sank with a loss of 1513 lives. It was one of the greatest disasters in maritime history. During the summer months the family often visited Catalan Bay where Diego José had a relative. On their way back home from the beach, The Gomez family were probably challenged by a sentry posted at Bayside, by the Laguna. The standard cry was, 'Officer, relief or inhabitant?' That year George V and his wife Queen Mary visited Gibraltar on their way back from India. There they entertained the Infante Don Carlos.

1913 Meanwhile the Governor, an austere man who made little effort to conceal his dislike of Gibraltar and its inhabitants, issued an arbitrary Fortress order forbidding Spanish workmen from returning home through Main Street. Policemen were posted at the Dockyard entrance to enforce the order. The local Chamber of Commerce was up in arms as the shops along Main Street stood to lose quite a bit of trade. A large demonstration was organised and a delegation was dispatched to London. The British Government acted swiftly, Sir Archibald was recalled, and two months later Lieutenant-General, Sir Herbert Miles took over as Governor.

1912 It was also a period when people could walk about at any hour without fear of being molested by drunken servicemen. Military discipline at the time was strict to the point of harshness. Nevertheless there was one occasion when Maria Luisa (2.4) and young Lina (1.2) were accosted by a drunken soldier. My mother later recalled indignantly that Maria Luisa had fled the scene leaving her alone to face the man, who fortunately was just mawkish drunk and well past violence.

Elsewhere tragedy struck. On the 12th of April, the 46 000 ton White Star liner Titanic struck an iceberg off Newfoundland on her maiden voyage and sank with a loss of 1513 lives. It was one of the greatest disasters in maritime history. During the summer months the family often visited Catalan Bay where Diego José had a relative. On their way back home from the beach, The Gomez family were probably challenged by a sentry posted at Bayside, by the Laguna. The standard cry was, 'Officer, relief or inhabitant?' That year George V and his wife Queen Mary visited Gibraltar on their way back from India. There they entertained the Infante Don Carlos.

1913 Meanwhile the Governor, an austere man who made little effort to conceal his dislike of Gibraltar and its inhabitants, issued an arbitrary Fortress order forbidding Spanish workmen from returning home through Main Street. Policemen were posted at the Dockyard entrance to enforce the order. The local Chamber of Commerce was up in arms as the shops along Main Street stood to lose quite a bit of trade. A large demonstration was organised and a delegation was dispatched to London. The British Government acted swiftly, Sir Archibald was recalled, and two months later Lieutenant-General, Sir Herbert Miles took over as Governor.

Lieutenant-General, Sir Herbert Scott Gould Miles

But protests and delegations apart, it was the illegality of his order that earned Hunter the sack. A defaulting Spanish workman was brought before the Chief Justice who ruled that the Order was invalid and had it repealed. The independence of the Judiciary as outlined in the Charter of 1831 had been put to the test and had not been found wanting.

It was shortly after these events that Diego José Gomez died in Gibraltar. A list of the funeral expenses was made up by his daughter Maria Luisa. The funeral charges were 93 Duros and his last will and testament, in which he left all his assets in equal shares to his four daughters, cost £13 16s 6d. Father Dodero's share of the loot for the privilege of saying Mass was 5 Duros. It was less expensive than the 8 Duros paid for the newspaper obituary. Maria Luisa made a note of a measly 'comision' of 2 Pesetas and 50 cents which was paid to a certain Mr. Leyvas. It is not known what the commission was for.

Apropos of the value of the commission, there was at that time a small Spanish coin with a hole in the middle which was worth a quarter of a peseta or 25 centimos. It was called a Real. Most country folk and working class people tended to calculate prices in Reales, a practice which was irritatingly awkward for the uninitiated.

Not that the British currency was any better. Farthings, ha'pennies, tiny silver thru penny pieces and marginally larger sixpenny coins called tanners were common tender. The shilling was called a bob and the two shilling piece a florin. For more expensive purchases there were somewhat bigger two shilling and sixpence pieces called half crowns. The enormous crown which was worth five shillings was also in use. The really well off, of course, elegantly calculated prices in guineas worth twenty one shillings.

There was also a sudden reversal of the situation of a few years back. There were now only 3 female apes left on the Rock. The Colonial Government agreed to the granting of a small fund for supplementing their food and the men of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, despite having better things to do undertook to supervise them.

It was shortly after these events that Diego José Gomez died in Gibraltar. A list of the funeral expenses was made up by his daughter Maria Luisa. The funeral charges were 93 Duros and his last will and testament, in which he left all his assets in equal shares to his four daughters, cost £13 16s 6d. Father Dodero's share of the loot for the privilege of saying Mass was 5 Duros. It was less expensive than the 8 Duros paid for the newspaper obituary. Maria Luisa made a note of a measly 'comision' of 2 Pesetas and 50 cents which was paid to a certain Mr. Leyvas. It is not known what the commission was for.

Apropos of the value of the commission, there was at that time a small Spanish coin with a hole in the middle which was worth a quarter of a peseta or 25 centimos. It was called a Real. Most country folk and working class people tended to calculate prices in Reales, a practice which was irritatingly awkward for the uninitiated.

Not that the British currency was any better. Farthings, ha'pennies, tiny silver thru penny pieces and marginally larger sixpenny coins called tanners were common tender. The shilling was called a bob and the two shilling piece a florin. For more expensive purchases there were somewhat bigger two shilling and sixpence pieces called half crowns. The enormous crown which was worth five shillings was also in use. The really well off, of course, elegantly calculated prices in guineas worth twenty one shillings.

There was also a sudden reversal of the situation of a few years back. There were now only 3 female apes left on the Rock. The Colonial Government agreed to the granting of a small fund for supplementing their food and the men of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, despite having better things to do undertook to supervise them.

Gibraltar from La Linea. A contemporary postcard.