Gibraltar Grammar School - Fuginakle

1949 It was also the year in which I took the so-called eleven-plus examination. This was basically an intelligence test that was taken by all children destined for state secondary education. The philosophy behind the test was based on the work of an English psychologist called Cyril Burt who was later duly knighted for his efforts. Much to the establishment's embarrassment, however, most of his research was later shown to have been fiddled to agree with his own preconceived prejudices.

According to this luminary, a child's intelligence was genetically determined with little hope for change after the age of eleven. The real reason why the eleven-plus was later abolished, however, was that too many middle-class children failed it and were sent to non-academic schools. In Gibraltar the penalty for failure was to be sent to the Secondary Modern School in Line Wall Road.

As I plodded my way through the exam I noticed that one of the questions involved finding out how long it took to do a particular task. It required some pretty fancy footwork. Seeing that the school clock was just alongside my desk I looked at it for a while hoping it would help me work out the answer. The invigilator immediately pounced and ticked me off in a loud voice, suggesting I would be better employed answering the questions than figuring out how much time I had left. Despite the embarrassment I passed the exam and joined the elite. I became a Grammar School Boy.

The Sacred Heart Grammar School and motto. Built with funds provided by Bishop Canilla in 1884, it eventually became a secondary school for boys. The photo shows what it looked like when I was there. The areas at the bottom and below the arches were used as playgrounds. Above the arched area there were the Physics and Chemistry Laboratories and the Art Room. When the Bedenham exploded in 1951 I was in the classroom on the second floor. The photograph shows five of its windows. The motto translates as ‘Stand Firm’.

The journey to and from my new school at the Sacred Heart took me four times daily through Library Ramp, a steep traffic-free passageway known locally as el Balali. There had been a Fives court there once, hence the local idiom for 'Ball Alley'. Two long semi-circular gutters ran along either side of the passageway and these were in constant use as race tracks for dinky toy cars. Soon after I began my secondary education, one of my toys became the school's champion racer. It withstood the challenges of all-comers for several months, until it was finally disqualified on the grounds that it was not in fact a car but a lorry. The disqualification was quite justified, as its much heavier weight was certainly responsible for most of its racing successes.

Another favourite schoolboy 'sport' of the period was cricket fighting. Its history goes back a thousand years: in China that is. In Gibraltar its origins were unknown. It was probably just a passing fad imported from Spain. The insects in question were always referred to as grillos and belonged to a species of ground crickets that had stout, shiny, dark brown bodies. I kept mine in a large matchbox well away from my less than enthusiastic mother who thought they looked like cockroaches. Luckily the crickets never lasted very long as fights were always to the death and even the winner rarely escaped without losing some important section of its anatomy. Getting the beasts in the mood involved making them run endlessly from hand to hand.

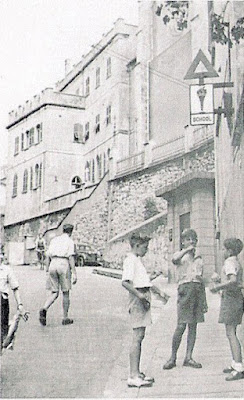

Later when the family moved South to Alameda House my journey to school; took a different path via Prince Edward's Road. To get to the school you had to turn sharp right just by the parked car.

Another favourite schoolboy 'sport' of the period was cricket fighting. Its history goes back a thousand years: in China that is. In Gibraltar its origins were unknown. It was probably just a passing fad imported from Spain. The insects in question were always referred to as grillos and belonged to a species of ground crickets that had stout, shiny, dark brown bodies. I kept mine in a large matchbox well away from my less than enthusiastic mother who thought they looked like cockroaches. Luckily the crickets never lasted very long as fights were always to the death and even the winner rarely escaped without losing some important section of its anatomy. Getting the beasts in the mood involved making them run endlessly from hand to hand.

Fighting crickets: an old print

Yet another activity that also involved creepy-crawlies was the rearing of silkworms. They were kept in shoe boxes and fed on choice mulberries leaves. By the time the poor beasts finally decided it was time to metamorphose into cocoons, interest would have begun to pall. It was time to deposit the shoebox and its contents down the rubbish shute.

Silkworms feeding on Mulberry leaves

Mercifully these cruel pastimes proved relatively short-lived and the children of Gibraltar soon turned their attentions to more conventional activities. One of these was the game of marbles. As they learned the game from the older boys, the children soon inherited a large vocabulary of the technical English terms used in the proper game. This despite the fact that the game played by the children was usually one of their own invention and bore little resemblance to the official version. Over the years the pronunciation of some of these terms had been distorted to such an extent that the actual words were hardly recognisable. To make matters worse they were often used out of context and were attributed a different meaning to that originally intended.

'Eres un fuginakle.' had moved a long way from 'fudging the nuckles'. The phrase was used to accuse someone of cheating. 'Kicks', or the longer version, 'Kicks por si pega', were called out when somebody wanted to do something that was not quite within the rules of whatever game was being played, not necessarily marbles. Shouting out 'No kicks' cancelled out 'kicks' and inferred an understandable refusal to countenance such blatant cheating.

The game itself was called lo' mebli, and the term el hijo del mebli was used to describe somebody who was considered a snob. Curiously the later term had nothing to do with the game of marbles. It referred to a certain Major Melby whose quarters were somewhere in the upper town and who seems to have made a habit of walking among the hoi polloi with his nose up in the air. All of which had happened quite a long time ago. But he must have made quite an impression hence the popular phrase which persisted for many years,

'¿Pero tu quien te ha' creido que ere', el hijo del Mebli?

'Eres un fuginakle.' had moved a long way from 'fudging the nuckles'. The phrase was used to accuse someone of cheating. 'Kicks', or the longer version, 'Kicks por si pega', were called out when somebody wanted to do something that was not quite within the rules of whatever game was being played, not necessarily marbles. Shouting out 'No kicks' cancelled out 'kicks' and inferred an understandable refusal to countenance such blatant cheating.

The game itself was called lo' mebli, and the term el hijo del mebli was used to describe somebody who was considered a snob. Curiously the later term had nothing to do with the game of marbles. It referred to a certain Major Melby whose quarters were somewhere in the upper town and who seems to have made a habit of walking among the hoi polloi with his nose up in the air. All of which had happened quite a long time ago. But he must have made quite an impression hence the popular phrase which persisted for many years,

'¿Pero tu quien te ha' creido que ere', el hijo del Mebli?

Marbles

When all else failed there was always the cinema. In those pre-television days, it was very much something to look forward to. It was extremely popular with both children and adults. Most people indulged at least twice every week. Many, including my mother, who invariably took me along with her, went even more frequently. A popular favourite was the old Naval Trust Cinema, which had a distinctive atmosphere all its own.

Perhaps it was the building itself which was a corrugated-iron structure which looked like an enormous and non-too-glorified Nissen hut. In fact during World War I it had been a sea-plane hanger.

The posh seats, which cost 1/6d, were bright red and stood symbolically on a slightly higher level than the 1/- and 6d ones patronised by the rabble below.

The posh seats, which cost 1/6d, were bright red and stood symbolically on a slightly higher level than the 1/- and 6d ones patronised by the rabble below.

During the interval they always played Waldteufel's España waltz just before the film was about to start. For many years afterwards, Gibraltarians of that generation would find it impossible to hear the tune without remembering the Naval. For good measure it was also the signature tune of the then Radio Gibraltar.

'Pum para pam pum pum,

pum pum para pam pum pum. . . . .'

It was sometime during the end of the forties that the place went up in a conflagration that can have had little to envy the Hindenburg disaster. Luckily there were no casualties. Several members of the family, however, were on hand to witness the total destruction of their favourite movie-house. They had probably intended going to see a film that day. The wind was blowing quite strongly and at one stage the flames threatened the tobacco factory at Chatham Counterguard. That would really have been something to remember.

'Pum para pam pum pum,

pum pum para pam pum pum. . . . .'

It was sometime during the end of the forties that the place went up in a conflagration that can have had little to envy the Hindenburg disaster. Luckily there were no casualties. Several members of the family, however, were on hand to witness the total destruction of their favourite movie-house. They had probably intended going to see a film that day. The wind was blowing quite strongly and at one stage the flames threatened the tobacco factory at Chatham Counterguard. That would really have been something to remember.

The Gibraltar Chronicle reports on the destruction of the Naval Trust Cinema

Later a new cinema, the Regal, was built in its place. But it was never the same. The Naval Trust was not the only cinema on the Rock at the time. The Rialto and the Theatre Royal were also much in demand. The Rialto was given to showing Spanish speaking films, some of which were Mexican melodramas of appalling quality. They were nevertheless often good value for money as many Gibraltarians often turned up simply to comment loudly on what was going on, laughing uproariously at the most inopportune moments. It could get quite funny at times as there were always people in the audience who actually enjoyed these films and took a dim view of the hecklers.

The Theatre Royal showed the usual mix of Hollywood musicals, comedies and dramas. It was a rather gloomy place perhaps best remembered for the Spanish vendor who was always to be found outside the entrance. Among the goodies which he dispensed in small paper cones to cinema-goers were altamuces, alcatufas, and garbanzos tostados. Altamuces - the proper Spanish name is altramuces - were boiled, oval, yellow pulses of some sort which were naturally salty and completely indigestible.

Because of their salty taste they were sometimes called salaitos. As a boy, Eric had once been strictly forbidden to eat them. The alcatufas or tiger nuts were sweet and probably equally disastrous from an intestinal point of view, while the toasted chickpeas were often dangerously hard on the teeth. Needless to say the vendor always made a roaring trade.

Altamuces, garbanzos and alcatufas

There was one other aspect of the Theatre Royal that also comes to mind. Anybody waiting to get in for the second performance usually hung about just below the wide exit-steps that led down from the theatre on to the street below. Then, as the muffled tones of the incidental music reached the climax that signalled the end of the film, there was a sudden seemingly catastrophic crash which sounded as if the ceiling had caved in. In fact the noise was caused by the exit-doors swinging open violently to disgorge a stampeding mass of people. They were trying to escape the tedium of having to stand still while the national anthem was being played.