Nylons - Haciendo el GDF

1947 The Colonial Annual Report showed that the civilian population now stood at 22 532, including 2 216 aliens. It was a time when it was practically impossible to buy dollars either in Britain or Gibraltar. It was also a time when American nylon stockings were in great demand and were very hard to come by in the U.K.

In Gibraltar they were easily available from Tangier which was an International free zone with considerable American influence. The local merchants soon spotted the enormous possibilities and began to advertise massively and systematically in the U.K. The result was an avalanche of postal orders. The nylons however could only be mailed singly, with a green label declaring the enclosures as a 'gift'.

1947 The Colonial Annual Report showed that the civilian population now stood at 22 532, including 2 216 aliens. It was a time when it was practically impossible to buy dollars either in Britain or Gibraltar. It was also a time when American nylon stockings were in great demand and were very hard to come by in the U.K.

In Gibraltar they were easily available from Tangier which was an International free zone with considerable American influence. The local merchants soon spotted the enormous possibilities and began to advertise massively and systematically in the U.K. The result was an avalanche of postal orders. The nylons however could only be mailed singly, with a green label declaring the enclosures as a 'gift'.

Nylons

One of the merchants involved was Giussepe Caruana. He had once rowed with Pepe in the MRC and knew Eric well. He offered my brother the part-time job of helping with the addressing of the envelopes. Very soon the whole family were involved night after night addressing envelopes to obscure places in Wales. It was a tedious job but the money came in handy.

Perhaps some of the extra money was spent at one of the local ferias. During the summer months, some of the larger towns in the campo area took turns to celebrate their annual fairs. The festivities usually included a series of bullfights in which big-name toreros took part. That very year, Manolete, the most famous matador of the era, was killed during one of these fairs in Linares, a town not all that far away from Gibraltar. He should have paid more attention to an often quoted ironic comment on his style of bullfighting, which was sung to the tune of a popular song of the era.

'Manolete, Manolete,

Si no sabes torear pa' que te mete.'

Perhaps some of the extra money was spent at one of the local ferias. During the summer months, some of the larger towns in the campo area took turns to celebrate their annual fairs. The festivities usually included a series of bullfights in which big-name toreros took part. That very year, Manolete, the most famous matador of the era, was killed during one of these fairs in Linares, a town not all that far away from Gibraltar. He should have paid more attention to an often quoted ironic comment on his style of bullfighting, which was sung to the tune of a popular song of the era.

'Manolete, Manolete,

Si no sabes torear pa' que te mete.'

Manolete in Pamplona shortly before his death. He was probably the best bullfighter of his generation but he was cold and calculating and there were many who didn’t like his style.

But there was more to the fairs than just bullfights. During the appropriate week, a section of the town was reserved for traditional fairground activities. In both La Linea and Algeciras it occupied a considerable area and was crammed with the usual paraphernalia of stalls, roundabouts, bumping cars, carousels, and roller-coasters.

The general appearance of almost all the attractions ranged from the rickety to the downright dangerous. There was one unforgettable and seemingly innocuous contraption called el latigo. It was a peculiarly shaped roundabout with a whip-like action, which was designed to make maximum use of centrifugal force. It was quite capable of unsettling the strongest of stomachs.

The fairs were, without exception, noisy, dusty, smelly and vulgar, but they were also curiously vibrant. At night they came into their own. As it grew darker, more and more lights were switched on and the crowds increased in number. The noise was appalling. Sirens screamed from the various attractions as they started and finished their rides. The intervals between these became shorter and shorter as the night wore on. Men with megaphones stood in front of huge stalls displaying hundreds of cheap, flashy prizes, urging every passer-by to gamble, throw, shoot, hit or simply just look at something or other. And over and above it all, a blanket of music from a hundred places, each playing their own particular gramophone record over and over again.

'Ay mi niña que te quiero, que te busco y no te encuentro..o..o

Y asi me paso la vi'a.

Ven a mi jardin, ven a mi jardin.'

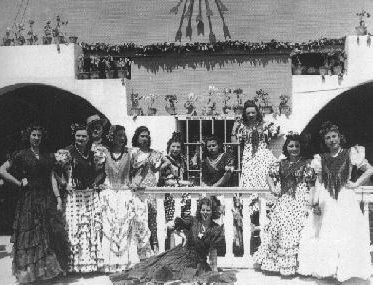

There were, here and there, one or two places of relative calm where people could dance or perhaps even sit down and have a drink. They were called casetas, and were sponsored by institutions of one sort or another. One of the most popular was run by Educacion y Descanso, the inappropriately named 'social club' of the local fascist party.

During the day, the casetas were often taken over by parents who were keen to show off their daughters wearing traditional Andalucian dresses. Although the girls were usually of primary school age, they were always heavily made up. These ghastly parodies, their tiny fingers sporting miniature castanets, always seemed more than willing to dance Sevillanas on the slightest provocation. The appropriate, but more than likely hypocritical response from anyone who happened to be passing by was,'¡Oy, pero que guapa está!'

The general appearance of almost all the attractions ranged from the rickety to the downright dangerous. There was one unforgettable and seemingly innocuous contraption called el latigo. It was a peculiarly shaped roundabout with a whip-like action, which was designed to make maximum use of centrifugal force. It was quite capable of unsettling the strongest of stomachs.

The fairs were, without exception, noisy, dusty, smelly and vulgar, but they were also curiously vibrant. At night they came into their own. As it grew darker, more and more lights were switched on and the crowds increased in number. The noise was appalling. Sirens screamed from the various attractions as they started and finished their rides. The intervals between these became shorter and shorter as the night wore on. Men with megaphones stood in front of huge stalls displaying hundreds of cheap, flashy prizes, urging every passer-by to gamble, throw, shoot, hit or simply just look at something or other. And over and above it all, a blanket of music from a hundred places, each playing their own particular gramophone record over and over again.

'Ay mi niña que te quiero, que te busco y no te encuentro..o..o

Y asi me paso la vi'a.

Ven a mi jardin, ven a mi jardin.'

There were, here and there, one or two places of relative calm where people could dance or perhaps even sit down and have a drink. They were called casetas, and were sponsored by institutions of one sort or another. One of the most popular was run by Educacion y Descanso, the inappropriately named 'social club' of the local fascist party.

During the day, the casetas were often taken over by parents who were keen to show off their daughters wearing traditional Andalucian dresses. Although the girls were usually of primary school age, they were always heavily made up. These ghastly parodies, their tiny fingers sporting miniature castanets, always seemed more than willing to dance Sevillanas on the slightest provocation. The appropriate, but more than likely hypocritical response from anyone who happened to be passing by was,'¡Oy, pero que guapa está!'

Caseta of Educacion y Descanso. Note the half hidden arrows at the top.

They were the symbols of La Falange, the Spanish fascist party.

They were the symbols of La Falange, the Spanish fascist party.

At night, formal invitations were often required for some of these casetas, but entry was difficult to control and gate-crashing was the norm rather than the exception. The most popular dances were the bolero, and the pasodoble. Elsewhere the noise continued unabated. Here and there people were drawn towards the aroma of red hot charcoal where they would find some Arab looking individual fanning away at a barbecue, grilling tiny pieces of skewered, marinated lamb, known locally as pinchitos. They were cooked and served under appallingly unhygienic conditions but were nevertheless delicious.

The stalls selling almendras garaspiñadas also produced their own distinctive smell of burning sugar. These caramel coated almonds were rock hard and were quite capable of breaking the healthiest tooth. When exhaustion finally set in, it was time to sit at one of the many fairground cafes. The thing to do was to order some small, doughnut shaped churros called buñuelos, which were traditionally dipped in hot chocolate.

In the month of July, Eric and Baba dutifully took me to what was probably the first of my many ferias in La Linea. It cannot have been much fun for my brother and sister, particularly in the sweltering heat of a summer afternoon, but for me it was sheer magic.

The stalls selling almendras garaspiñadas also produced their own distinctive smell of burning sugar. These caramel coated almonds were rock hard and were quite capable of breaking the healthiest tooth. When exhaustion finally set in, it was time to sit at one of the many fairground cafes. The thing to do was to order some small, doughnut shaped churros called buñuelos, which were traditionally dipped in hot chocolate.

In the month of July, Eric and Baba dutifully took me to what was probably the first of my many ferias in La Linea. It cannot have been much fun for my brother and sister, particularly in the sweltering heat of a summer afternoon, but for me it was sheer magic.

Paseo de La Velada. This old postcard shows the area of La Linea where the fair was always held. On fair days these entrance arches were lit up at night.

Note the bullring in the background.

Note the bullring in the background.

La Feria at night - memorable!

The Chipulinas were not the only ones with money problems. Pay differentials between Gibraltarians and ex-Pats doing the same job were a sore point at the time as this occurred not just at executive but at all other levels as well. The invariable and unconvincing excuse was that ex-pats required a 'foreign allowance'. The situation was even worse for Spanish nationals.

Now that the war was over, far fewer Spanish dockyard workers were required. Nevertheless with the return of the civilian population there was great demand for building and other labourers as well as for female domestic workers. Over the next few years the average number of workers crossing from Spain on a daily basis was around 12 000.

Generally Spanish workers were paid about 60% of what a corresponding Gibraltarian employee would have been paid. There was little protection against arbitrary dismissal, and even less compensation for accidents at work. In many establishments Spanish workers were required to use separate toilets, although this had probably more to do with white collar, blue collar relationships than with differences of nationality. The absurd psychology relating to the executive's status symbol dream of having a separate toilet for himself, seems to have been as valid in Gibraltar as anywhere else in the world

This state of affairs, however, was not universal. The Shell Oil Company which at the time was probably the second largest employer of Spanish labour in the private sector paid all their workers according to grade regardless of nationality. Social insurance was compulsory, with the Company paying the lion's share of the contributions. It included injury benefit and dismissals were neither more nor less unfair for Spaniards than they were for anyone else.

The ease with which Spanish workers could cross into and out of Gibraltar made possible the organization of a guerrilla group on the Rock, without the knowledge of the British authorities. In August they crossed over into Spain and operated for several years in the area around Algeciras, Jimena, Gaucin and Ronda.

For many years afterward any Gibraltarian driving to Madrid or some place in the north of Spain by car, would always cast a wary look out of the window when travelling through the gorge at Despeñaperros, half expecting to be held up by some of these guerillas.

Now that the war was over, far fewer Spanish dockyard workers were required. Nevertheless with the return of the civilian population there was great demand for building and other labourers as well as for female domestic workers. Over the next few years the average number of workers crossing from Spain on a daily basis was around 12 000.

Generally Spanish workers were paid about 60% of what a corresponding Gibraltarian employee would have been paid. There was little protection against arbitrary dismissal, and even less compensation for accidents at work. In many establishments Spanish workers were required to use separate toilets, although this had probably more to do with white collar, blue collar relationships than with differences of nationality. The absurd psychology relating to the executive's status symbol dream of having a separate toilet for himself, seems to have been as valid in Gibraltar as anywhere else in the world

This state of affairs, however, was not universal. The Shell Oil Company which at the time was probably the second largest employer of Spanish labour in the private sector paid all their workers according to grade regardless of nationality. Social insurance was compulsory, with the Company paying the lion's share of the contributions. It included injury benefit and dismissals were neither more nor less unfair for Spaniards than they were for anyone else.

The ease with which Spanish workers could cross into and out of Gibraltar made possible the organization of a guerrilla group on the Rock, without the knowledge of the British authorities. In August they crossed over into Spain and operated for several years in the area around Algeciras, Jimena, Gaucin and Ronda.

For many years afterward any Gibraltarian driving to Madrid or some place in the north of Spain by car, would always cast a wary look out of the window when travelling through the gorge at Despeñaperros, half expecting to be held up by some of these guerillas.

Despeñaperros

Meanwhile, Willie Vacca, who had by now become a U.S. Citizen, still kept in touch with Lina. He had a daughter called Lucille, worked for a firm of packers and seemed to have carved for himself a reasonably comfortable existence in the good old U.S. of A. At Christmas he often sent us typical American candy. The most memorable was a pecan cake densely packed with fruit and nuts. It came inside a beautifully decorated tin. He also sent give-away articles such as pen-knives and letter openers as well as glossy American magazines.

Many an evening I would pore over them, enviously pining for the abundance of that American way of life. It was, of course, the advertisements which made the greatest impression. In the U.S.A. it seemed to me, everybody was tall, young, tanned and healthy, drank litres of orange juice for breakfast, lived in clean modern houses with every convenience imaginable, and drove around in massively chromium-plated cars.

By now I had become the kind of small boy who was rarely at a loss for something to do and was always totally absorbed in whatever it was I was doing. In moments of supreme concentration I would never bite my tongue like many other children do. Instead my upper lip would slowly climb over the lower one and my face would take on an expression which greatly amused my mother. Even at that early age I was already a voracious, if rather unselective, reader always looking forward to accompanying my sister to the local Lending Library. Here I would spend an enjoyable half-hour selecting the five or six books I would need to replace those I had read the previous week. It was a love for reading which I had inherited from the rest of my family and which I would retain till the present day.

Many an evening I would pore over them, enviously pining for the abundance of that American way of life. It was, of course, the advertisements which made the greatest impression. In the U.S.A. it seemed to me, everybody was tall, young, tanned and healthy, drank litres of orange juice for breakfast, lived in clean modern houses with every convenience imaginable, and drove around in massively chromium-plated cars.

By now I had become the kind of small boy who was rarely at a loss for something to do and was always totally absorbed in whatever it was I was doing. In moments of supreme concentration I would never bite my tongue like many other children do. Instead my upper lip would slowly climb over the lower one and my face would take on an expression which greatly amused my mother. Even at that early age I was already a voracious, if rather unselective, reader always looking forward to accompanying my sister to the local Lending Library. Here I would spend an enjoyable half-hour selecting the five or six books I would need to replace those I had read the previous week. It was a love for reading which I had inherited from the rest of my family and which I would retain till the present day.

The Lending Library. The main building in the photograph is the local Magistrates court. The large palm tree on the left hides the entrance to what used to be the Lending Library.

If reading for pleasure depends on the ability to create ones own illusionary world out of somebody else’s written words, then I definitely had this ability. Even more so my brother and not just with words. As a youngster, Eric made use of almost anything that could be made to stand up straight to represent soldiers, soccer players or whatever a particular game required. He sometimes even resorted to using long screws with large enough heads to represent people. Empty match boxes with the odd match sticking out here and there could be made to look like a car, a tank or even a motor cycle. It took me very little time to latch on to the idea.

My most popular 'toy' at the time was a large set of flat wooden blocks, leftovers from the Art Shop, and which for some obscure reason were referred to by the family as 'blinking blocks'. Their tops carefully painted in the strips of various first division English football teams, they quickly acquired a life of their own and were soon producing some of the finest soccer matches ever seen on this planet. A continuous guttural hiss from the back of the throat, which rose to a crescendo when goals were scored, represented the roar of the crowd. Attendances of more than one hundred thousand were commonplace at 256 Main Street.

To my enormous delight Eric would sometimes take part in some of the games. Unfortunately as time passed and Eric grew older, these already rare interventions became less and less frequent until finally and sadly, as with all good things, they came to an end.

My most popular 'toy' at the time was a large set of flat wooden blocks, leftovers from the Art Shop, and which for some obscure reason were referred to by the family as 'blinking blocks'. Their tops carefully painted in the strips of various first division English football teams, they quickly acquired a life of their own and were soon producing some of the finest soccer matches ever seen on this planet. A continuous guttural hiss from the back of the throat, which rose to a crescendo when goals were scored, represented the roar of the crowd. Attendances of more than one hundred thousand were commonplace at 256 Main Street.

To my enormous delight Eric would sometimes take part in some of the games. Unfortunately as time passed and Eric grew older, these already rare interventions became less and less frequent until finally and sadly, as with all good things, they came to an end.

The ‘blinking blocks’

Eric, in fact, had other things on his mind. He was now well into his National Service. Eric was temperamentally unsuited to military life and generally tended to treat life at Buena Vista Barracks as one long, absurd joke. Being an excellent raconteur, he would often amuse the rest of the family with humorous anecdotes on the idiosyncrasies of British military life.

On one occasion, for example, the army in its wisdom decided to pack the entire intake into a small Nissen hut in order to give them a lecture. As it was a cold, rainy day, all the windows were tightly shut. Meanwhile the audience puffed away, as they chain-smoked to relieve their boredom. By the time the proceeding got under way the air in the room was thick enough to cut with the proverbial knife. Needless to say the lecturer was the Medical Officer, and the subject was on 'Health and Hygiene'.

One of the many characters in Eric's intake was Levito Attias, a born comedian who would subsequently become a professional television actor, taking part in the comedy series 'Mind Your Language' and other well known U.K. productions. One evening the intake was watching a film when suddenly the lights went on and an officer stood by the door. He had touched the doorway switch mechanically, and was probably embarrassed at having interrupted the film. Feeling that some sort of explanation was required of him he introduced himself.

'I'm.. er.. Captain Smith'.

Levi, who happened to be sitting just next to the door, immediately rose to his feet and shook him warmly by the hand.

'Hello, I'm Levy Attias,' he said with an impeccable Oxford accent.' How do you do'.

The official highlight for that year's intake was the annual ritual of the Ceremony of the Keys which was held at the Casemates. It was the first time that a local contingent was allowed to be involved in this or any other ceremonial occasion. Presumably the authorities had finally conceded that after a suitable number of hours of square bashing, Gibraltarians could be relied upon to march in step. The weekly ritual of La retreta, however, in which a military band marched down Main Street, was still very much in the hands of the resident British regiments.

By now the event had become purely ceremonial. Some regiments had a mascot, notably the Royal Welsh Fusiliers whose band was always headed by a beautiful white goat with its horns wrapped in gold foil. The locals called them El regimiento de la cabra. Scottish regiments on the other hand were always preceded by the wail of their own bagpipes. They were usually referred to as Enaquetas. The Scottish soldiers would probably have been quite upset if they had realised that the word is derived from the Spanish word for a skirt.

In almost all the regimental bands the man who beat the big drum wore a leopard skin draped over his shoulders. It was a strange military tradition which the British had pinched from 18th century Turkey where the slave Negro drummers of the Sultan always went on parade wearing exotic native uniforms.

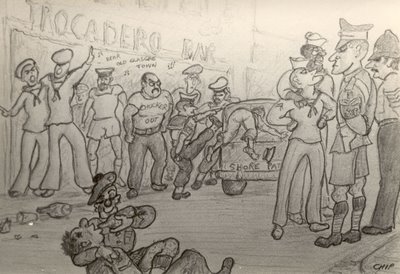

1948 At the time, however, Gibraltar had other more contemporary animals to contend with. When the fleet was in port, Main Street became almost impassable with literally thousands of drunken sailors staggering up and down the main thoroughfare. For the locals, getting from one place to another in the evening could be something of a hazard. The establishments that catered for the Navy's unquenchable thirst were 'wild west' type saloon bars complete with swing doors. One of these, the Trocadero was just down the road from 256 Main Street.

On one occasion, for example, the army in its wisdom decided to pack the entire intake into a small Nissen hut in order to give them a lecture. As it was a cold, rainy day, all the windows were tightly shut. Meanwhile the audience puffed away, as they chain-smoked to relieve their boredom. By the time the proceeding got under way the air in the room was thick enough to cut with the proverbial knife. Needless to say the lecturer was the Medical Officer, and the subject was on 'Health and Hygiene'.

One of the many characters in Eric's intake was Levito Attias, a born comedian who would subsequently become a professional television actor, taking part in the comedy series 'Mind Your Language' and other well known U.K. productions. One evening the intake was watching a film when suddenly the lights went on and an officer stood by the door. He had touched the doorway switch mechanically, and was probably embarrassed at having interrupted the film. Feeling that some sort of explanation was required of him he introduced himself.

'I'm.. er.. Captain Smith'.

Levi, who happened to be sitting just next to the door, immediately rose to his feet and shook him warmly by the hand.

'Hello, I'm Levy Attias,' he said with an impeccable Oxford accent.' How do you do'.

The official highlight for that year's intake was the annual ritual of the Ceremony of the Keys which was held at the Casemates. It was the first time that a local contingent was allowed to be involved in this or any other ceremonial occasion. Presumably the authorities had finally conceded that after a suitable number of hours of square bashing, Gibraltarians could be relied upon to march in step. The weekly ritual of La retreta, however, in which a military band marched down Main Street, was still very much in the hands of the resident British regiments.

By now the event had become purely ceremonial. Some regiments had a mascot, notably the Royal Welsh Fusiliers whose band was always headed by a beautiful white goat with its horns wrapped in gold foil. The locals called them El regimiento de la cabra. Scottish regiments on the other hand were always preceded by the wail of their own bagpipes. They were usually referred to as Enaquetas. The Scottish soldiers would probably have been quite upset if they had realised that the word is derived from the Spanish word for a skirt.

In almost all the regimental bands the man who beat the big drum wore a leopard skin draped over his shoulders. It was a strange military tradition which the British had pinched from 18th century Turkey where the slave Negro drummers of the Sultan always went on parade wearing exotic native uniforms.

1948 At the time, however, Gibraltar had other more contemporary animals to contend with. When the fleet was in port, Main Street became almost impassable with literally thousands of drunken sailors staggering up and down the main thoroughfare. For the locals, getting from one place to another in the evening could be something of a hazard. The establishments that catered for the Navy's unquenchable thirst were 'wild west' type saloon bars complete with swing doors. One of these, the Trocadero was just down the road from 256 Main Street.

The Trocadero Bar, Main Street Gibraltar. This was one of several establishments that catered for the Navy. In the photo a group of British sailors loiter with intent as they try to figure out a way to get past the well armed shore patrol man blocking their way into the bar. Note the number of the shop next door. The Trocadero was 240 and our house was 256 or just seven doorways to the left of where the sailors are standing. When the American 6th coincided in port with the British Mediterranean Fleet things could become quite unpleasant for anybody living close to the Trocadero.

The Trocadero had a resident band that played from opening time to 11 o'clock at night. As the evening wore on, the overworked musicians inevitably began to sound like an old gramophone record that needed rewinding. Meanwhile the choir from within would grow ever more vociferous and the melodies less and less coherent. If the door of one of these establishments happened to swing open as you passed by, you were almost overpowered by the stench of cheap beer and stale vomit.

Outside stood the Law. The normal complement was made up of several nasty looking Redcaps and some even nastier looking R.A.F. police. A few civilian coppers, a pair of professional looking thugs from the Naval Depot and a group of rather sheepish Ship's Police often kept them company. When closing time came the real action began. The swing doors would open with a crash and out came a raucous melee of uniformed men, some still trying to settle some argument or other. The majority were determined to carry on their singing in the open air without the benefit of music.

Meanwhile the Law would step into the premises to carry out its nightly mopping up operation. There were plenty of trucks and vans available for the various police forces to toss the over-quarrelsome, the unrepentant or the just plain dead drunk. It was all done with about as much fuss as a stevedore loading potatoes into a lorry.

For the next hour or so, however, all roads leading to either the warships or the barracks, would resound with out-of-tune renderings of old favourites such as 'I Belong to Glasgow', 'The Bells are Ringing for Me and My Girl, and 'Bless 'Em All'. In the case of the latter the verb was often drastically changed. Anyone who lived in Main Street and was returning home late had to learn very quickly how to run the gauntlet of this often unreasonable, always objectionable, mass of drunken humanity.

Outside stood the Law. The normal complement was made up of several nasty looking Redcaps and some even nastier looking R.A.F. police. A few civilian coppers, a pair of professional looking thugs from the Naval Depot and a group of rather sheepish Ship's Police often kept them company. When closing time came the real action began. The swing doors would open with a crash and out came a raucous melee of uniformed men, some still trying to settle some argument or other. The majority were determined to carry on their singing in the open air without the benefit of music.

Meanwhile the Law would step into the premises to carry out its nightly mopping up operation. There were plenty of trucks and vans available for the various police forces to toss the over-quarrelsome, the unrepentant or the just plain dead drunk. It was all done with about as much fuss as a stevedore loading potatoes into a lorry.

For the next hour or so, however, all roads leading to either the warships or the barracks, would resound with out-of-tune renderings of old favourites such as 'I Belong to Glasgow', 'The Bells are Ringing for Me and My Girl, and 'Bless 'Em All'. In the case of the latter the verb was often drastically changed. Anyone who lived in Main Street and was returning home late had to learn very quickly how to run the gauntlet of this often unreasonable, always objectionable, mass of drunken humanity.

The Trocadero.. The cartoon is one of several drawn by Eric Chipulina for a series of articles called ‘A Short Expedition into the Gibraltarian Mind’. It was published in the Gibraltar Chronicle.

The USS Valley Forge. This enormous American aircraft carrier called at Gibraltar harbour on her trip around the world. The photo shows the main entrance to the Gibraltar Dockyards. The road on the bottom left leads towards the Alameda Gardens. The house in Red Sands Road that my family would move to had not yet been built.

When the fates decreed that some American Fleet or other should coincide in port with an equally large British unit, things could become thoroughly unpleasant. It was by no means a rare event for a member of the Chipulina family to return home and find that several individuals of linebacker proportions had decided to settle their differences outside the front door of 256. Indeed it is part of the family’s collective memory to recall falling blissfully asleep night after night to the chorus of 'I Belong to Glasgow', safe in the knowledge that it was absolutely impossible for the buggers to get into the house.

Meanwhile Gibraltar kept trying to improve its image. During the war the enemy had not really caused any significant damage to the Rock. Nevertheless the town was beginning to show signs of wear and tear. Over a period of time the Colonial Government began to draw up a complex but ineffective Town Plan. Significantly they consulted Professor Hayek, a radical right wing conservative who was later to become famous for advising Mrs. Thatcher. Thankfully, unlike Mrs. Thatcher, the local authorities never put any of his monetarist theories into practice.

The Colonal Annual Report showed that the civilian population was still on the increase. It stood at 23 700, including 2 228 aliens. Local politics were hotting up and the AACR began to agitate and demand the creation of both Legislative and Executive Councils. At the same time, far from the madding crowd, Gorham's cave was excavated. The work revealed four levels of occupation from Neanderthal to Roman times. Elsewhere remains collected from other caves and fissures revealed the presence at some time in the very distant past of 25 species of mammals, including the elephant, the rhinoceros and the panther: an incredible collection for such a small place.

Meanwhile Gibraltar kept trying to improve its image. During the war the enemy had not really caused any significant damage to the Rock. Nevertheless the town was beginning to show signs of wear and tear. Over a period of time the Colonial Government began to draw up a complex but ineffective Town Plan. Significantly they consulted Professor Hayek, a radical right wing conservative who was later to become famous for advising Mrs. Thatcher. Thankfully, unlike Mrs. Thatcher, the local authorities never put any of his monetarist theories into practice.

The Colonal Annual Report showed that the civilian population was still on the increase. It stood at 23 700, including 2 228 aliens. Local politics were hotting up and the AACR began to agitate and demand the creation of both Legislative and Executive Councils. At the same time, far from the madding crowd, Gorham's cave was excavated. The work revealed four levels of occupation from Neanderthal to Roman times. Elsewhere remains collected from other caves and fissures revealed the presence at some time in the very distant past of 25 species of mammals, including the elephant, the rhinoceros and the panther: an incredible collection for such a small place.

1948 - The Austin A90 'Atlantic' - A misquided and short lived attempt to offer a car that would appeal to the American market