Pensao Boavista - A Letter to My Love

1943 I was now nearly five. Like many children of that age I was fond of scribbling and was always asking for a pencil. If I was offered a coloured pencil when what I really wanted was a lead one, I would dismiss the offering and demand 'an ornery pessus'. Another curious expression was 'I'm c'ftable' which I seem to have used whenever I was feeling particularly uncomfortable. Both these expressions greatly amused my mother who would mimic both my pronunciation and the rather pained expression on my face when she retold the incidents to other members of the family.

By now I was also learning how to recite and recognize the alphabet. One day, while reading the letters out from a book, I paused for a minute and looked up. 'Which one,' I asked with a mildly puzzled expression, 'is 'lemeno'? '

It was also around this period that I made my first real friends. There was a little girl called Patsi Pitto who was known to everyone as Pachucha, and just across the road lived Tito Torres who was later to be one of my best schoolboy friends.

1943 I was now nearly five. Like many children of that age I was fond of scribbling and was always asking for a pencil. If I was offered a coloured pencil when what I really wanted was a lead one, I would dismiss the offering and demand 'an ornery pessus'. Another curious expression was 'I'm c'ftable' which I seem to have used whenever I was feeling particularly uncomfortable. Both these expressions greatly amused my mother who would mimic both my pronunciation and the rather pained expression on my face when she retold the incidents to other members of the family.

By now I was also learning how to recite and recognize the alphabet. One day, while reading the letters out from a book, I paused for a minute and looked up. 'Which one,' I asked with a mildly puzzled expression, 'is 'lemeno'? '

It was also around this period that I made my first real friends. There was a little girl called Patsi Pitto who was known to everyone as Pachucha, and just across the road lived Tito Torres who was later to be one of my best schoolboy friends.

Me and my first girl friend Patti Pitto. At the back of the photograph somebody has written: ‘ Atlantic Hotel 24th June 1943’. The photograph was probably taken by Patti’s mother. The posing is unlike that of most of the other snapshots taken at the time.

That summer my father was beginning to grow visibly weaker. The fact that he had always enjoyed a strong constitution worked against him, prolonging the agony. He ended up a living skeleton, with alternating intervals of lucidity and delirium. He finally died in August and was buried in Sao Martinho Cemetery, right at the top of Barreiros hill. His pension of about 6 pounds a month from the Cable and Wireless did not pass on to his widow.

Me posing on one of the balconies of the Atlantic Hotel. It was taken shortly before my father died. On the back of the photograph my mother wrote: ‘To my dear daddy.’ I imagine she was fearing the worst.

Madeira.On the back of the photo my mother has written: 'Lavinia’s Party, Madeira 1943.' Lavinia was a very vivacious girl. She is the one with the Spanish costume. Her brother Jimmy stands on her left. I am second from the right on the front row with my friend Tito Torres on my right. The boy just behind Lavinia is her cousin Charlie Cruz. He would later become another good friend.

My brother Eric and I. This was taken somewhere in the Atlantic Hotel. Despite his short trousers my brother appears to be uncharacteristically well dressed. This is one of the few photos of me and my brother together. The difference of ten years in our respective ages meant that we rarely moved in the same circles.

Madeira.On the back of the photo my mother has written: 'Lavinia’s Party, Madeira 1943.' Lavinia was a very vivacious girl. She is the one with the Spanish costume. Her brother Jimmy stands on her left. I am second from the right on the front row with my friend Tito Torres on my right. The boy just behind Lavinia is her cousin Charlie Cruz. He would later become another good friend.

My brother Eric and I. This was taken somewhere in the Atlantic Hotel. Despite his short trousers my brother appears to be uncharacteristically well dressed. This is one of the few photos of me and my brother together. The difference of ten years in our respective ages meant that we rarely moved in the same circles.

My mother had been exceptionally pretty in her youth. Now 43, she had retained her good looks, her slim figure and her reddish-brown hair. In fact she looked much younger than she was. Generally, she had a warm unassertive personality, but in that apparent softness lay embedded streaks of flint. Her grey-green eyes could take on a cold, menacing glint when she was angry, and on those very rare occasions when she was truly aroused, she was metaphorically capable of facing a tiger. In fact there was a certain dichotomy to her personality.

A naturally strong character, she had often been inhibited by the circumstances of her life. Her mother, Maria Luisa (2.4) , who was always in the offing, was not only also a strong character, but bossy, abrasive and irritatingly perverse. When Lina(1.2) married Pepe (1.2), another strong personality, he and his mother-in-law, who had lived with them, co-existed on a permanent war-footing. Lina (1.2) was often caught in the cross-fire, and soon developed the tactic of being as unobtrusive as possible, a case of 'anything for a quiet life' as the saying goes. The habit probably became second nature.

Perhaps the true measure of her strength of character can be judged by the way she coped at the time, and in subsequent years, when she suddenly found herself in a foreign land, widowed, with three young children to bring up and without a penny to her name. And Maria Luisa (2.4) was still around. The family now moved even further down the scale of categories for refugees. From partly subsidised they were now considered worthy of being totally subsidised. The Chipulina family had entered the ranks of the Gibraltar poor.

A naturally strong character, she had often been inhibited by the circumstances of her life. Her mother, Maria Luisa (2.4) , who was always in the offing, was not only also a strong character, but bossy, abrasive and irritatingly perverse. When Lina(1.2) married Pepe (1.2), another strong personality, he and his mother-in-law, who had lived with them, co-existed on a permanent war-footing. Lina (1.2) was often caught in the cross-fire, and soon developed the tactic of being as unobtrusive as possible, a case of 'anything for a quiet life' as the saying goes. The habit probably became second nature.

Perhaps the true measure of her strength of character can be judged by the way she coped at the time, and in subsequent years, when she suddenly found herself in a foreign land, widowed, with three young children to bring up and without a penny to her name. And Maria Luisa (2.4) was still around. The family now moved even further down the scale of categories for refugees. From partly subsidised they were now considered worthy of being totally subsidised. The Chipulina family had entered the ranks of the Gibraltar poor.

Maruja swimming somewhere in Madeira seemingly oblivious to the fact that the family had now entered the ranks of the poor When my sister sent me this photo she commented that a friend of hers – the type who likes to read ‘Hola’ and such like magazines - had told her that she had a photo of her in which she looked like a film star. This was the photo. Could it have been Ester Williams she was thinking about perhaps?

The owner of the Atlantic Hotel, Dr. Eça, offered Lina a reduced rate if she would stay. It was a nice gesture but she refused. The episode demonstrates the complexities of human nature. In contrast to his kindness to Lina, Dr. Eça was a notorious despot, a natural fascist who treated his staff as if they were serfs. He was known to have slapped a waiter's face for the heinous crime of being late in taking his master's breakfast to his room.

Me and some of my friends. This was taken in one of the balconies of the Atlantic Hotel. The original untinted photo is dated 1941 but I think it was probably taken in early 1943. Tito Torres stands in the middle looking really pleased with himself. I think he fancied his get-up. Behind him is Albert Brooks while I stand on the right looking rather sheepish. I don’t remember the name of the fourth boy.

There were also of course, real political fascists in Madeira at the time. In Funchal there was a local branch of a uniformed organization called Moçedades Portuguesa. They were easily recognised by their green shirts, brown pants and ankle-length boots. They held regular rallies in which the local Führer as often as not would exhort his troops by asking them to confirm their unwavering loyalty.

Leader: 'Portugueses, quien vive?'

Troops: 'Portugal, Portugal, Portugal!'

Leader: 'Portugueses, quien manda?'

Troops: 'Salazar, Salazar, Salazar!'

There were also Eric's unspoken thoughts as he listened respectfully from a prudently distant vantage point;

'Tu y tu puta madre.'

Leader: 'Portugueses, quien vive?'

Troops: 'Portugal, Portugal, Portugal!'

Leader: 'Portugueses, quien manda?'

Troops: 'Salazar, Salazar, Salazar!'

There were also Eric's unspoken thoughts as he listened respectfully from a prudently distant vantage point;

'Tu y tu puta madre.'

Tito Torres’ birthday party in the Atlantic Hotel. Tito is in the first row fifth from the left. Albert Brooks is on the right with a dark pullover. I am kneeling on the left with a grey jersey. On the back of the card there is an inscription which reads : ‘To Neville with love from Ernestito 16.5.43’. I remember this party very well. We played a game in which we formed a circle. One of us then stood in the middle while the children in the circle passed a letter secretly to one another behind their backs. The child in the middle tried to figure out who had the letter. Meanwhile we all sang a song that went like this: 'I sent a letter to my love, and on the way I dropped it, A little puppy picked it up and put it in his pocket. It isn't you, it isn't you, it isn't you, it isn't you . . . . . . . . . it’s you!!!

A Portuguese friend of Maruja had once been a supporter of Moçedades. His full name was Manoel da Silva Rodrigues. He was known to his friends as Manecas. Maruja first met him at the Lido where he had been hanging about looking rather silly in a natty one piece bathing suit with the letters MP - Moçedades Portuguesa - emblazoned across his chest. His membership ofMoçedades did not necessarily reflect his political ideals. At that time Portugal was a one party state and practically everybody his age belonged as a matter of course. In fact he turned out to be a very pleasant young man with the usual Portuguese penchant for impeccable manners. He soon became a close friend.

One day Manecas invited Maruja and her friend Irene Torres to his summer house. As the girls approached the place they were confronted by a muddy yard with several wary looking pigs wallowing about in the dirt. After some hesitation Irene took the plunge and strode across the yard. She ended up knee deep in the stuff and the thoroughly embarrassed host was forced to pick her up and carry her towards safety. Manecas eventually joined the navy as a cadet and became a member of the Portuguese equivalent of the Fleet Air Arm. He spoke excellent English thus ensuring that Maruja would learn very little Portuguese during her stay in Madeira.

In September Marshal Badoglio took over from Mussolini. Italy surrendered, the Armistice was signed and the Italians changed sides. The occasion was celebrated in Gibraltar by a great ack-ack searchlight display. Italy had been the main instigator of attacks on Gibraltar during the war, both by air and by sea. Despite this, the Italians had never been much feared for their fighting qualities. Their large and modern navy for example was scarcely ever put to any use. A joke doing the rounds at the time asked the question.

'¿Cuales son las tres cosas mas inutiles del mundo?'

To which the reply was,

'Las tetas de un hombre, los cojones del Papa, y la escuadra Italiana.'

One day Manecas invited Maruja and her friend Irene Torres to his summer house. As the girls approached the place they were confronted by a muddy yard with several wary looking pigs wallowing about in the dirt. After some hesitation Irene took the plunge and strode across the yard. She ended up knee deep in the stuff and the thoroughly embarrassed host was forced to pick her up and carry her towards safety. Manecas eventually joined the navy as a cadet and became a member of the Portuguese equivalent of the Fleet Air Arm. He spoke excellent English thus ensuring that Maruja would learn very little Portuguese during her stay in Madeira.

In September Marshal Badoglio took over from Mussolini. Italy surrendered, the Armistice was signed and the Italians changed sides. The occasion was celebrated in Gibraltar by a great ack-ack searchlight display. Italy had been the main instigator of attacks on Gibraltar during the war, both by air and by sea. Despite this, the Italians had never been much feared for their fighting qualities. Their large and modern navy for example was scarcely ever put to any use. A joke doing the rounds at the time asked the question.

'¿Cuales son las tres cosas mas inutiles del mundo?'

To which the reply was,

'Las tetas de un hombre, los cojones del Papa, y la escuadra Italiana.'

Badoglio’s message of surrender by radio to the Italian nation

The Italian POW's in Gibraltar became the Italian Pioneer Corp. attached to Royal Engineers. They wore British battledress with the letters IPC on their shoulder flashes. Inevitably the local wits interpreted these as 'Ingleses Por Cojones'. Some of them were excellent craftsmen and undertook private work for civilians.

In October, a Spaniard called Jose Martin Muñoz was arrested while trying to smuggle a bomb into the Rock. He was brought to trial and sentenced to death. The trial lasted 15 minutes. The official Home Office executioner, Albert Pierrepoint, flew to Gibraltar to perform the executions of the two Spanish spies, Cordon-Cuenca, and Muñoz. After being hung from a specially constructed scaffold both were buried within the prison walls.

That month George Formby livened things up somewhat and did his bit for the war effort when he entertained at the Gibraltar Military Hospital. Hopefully he had moved on from his 'phoney war' hit:

'Imagine me in the Maginot Line,

Sitting on a mine

In the Maginot Line.'

Throughout the war ENSA parties came regularly to Gibraltar, either to perform or on their way elsewhere. Even after the war they continued visiting the Rock. Their shows at the Theatre Royal were gloriously vulgar affairs clearly tailored for the troops.

Meanwhile the Chipulina family was still in the Atlantic Hotel when Madeira experienced an earthquake. Despite the island's volcanic origins, earthquakes were by no means common. In fact this was the only one they experienced during their time there. I can remember sitting in the dining room of the hotel with my mother having lunch when it happened. The sensation was that of a very heavy lorry passing by and was in fact mistaken as such by both of us until all was revealed later that evening.

Soon after, the family moved to a small pension called Pensao Boavista in Rua Carreira. Boavista was something of a misnomer, but it was comfortable, very close to the centre of town, and within walking distance of the school. It was also quite close to the Headquarters of the 'Policia para Vigilança e Defensa do Estado', the PVDE. It was said that when the police band was practising in the patio it meant that some poor fellow was getting a hiding in the cells.

The food at the Pensao, which was dull but adequate, was occasionally supplemented by Lina with 'goodies' from a German Jewish delicatessen called Bach Irmaos which stood at the street corner. Their liver sausage was a particularly delicious item. Sunday treats included cakes from an Italian Patisserie at the other corner of the street followed by a film at the Teatro Municipal.

In October, a Spaniard called Jose Martin Muñoz was arrested while trying to smuggle a bomb into the Rock. He was brought to trial and sentenced to death. The trial lasted 15 minutes. The official Home Office executioner, Albert Pierrepoint, flew to Gibraltar to perform the executions of the two Spanish spies, Cordon-Cuenca, and Muñoz. After being hung from a specially constructed scaffold both were buried within the prison walls.

That month George Formby livened things up somewhat and did his bit for the war effort when he entertained at the Gibraltar Military Hospital. Hopefully he had moved on from his 'phoney war' hit:

'Imagine me in the Maginot Line,

Sitting on a mine

In the Maginot Line.'

Throughout the war ENSA parties came regularly to Gibraltar, either to perform or on their way elsewhere. Even after the war they continued visiting the Rock. Their shows at the Theatre Royal were gloriously vulgar affairs clearly tailored for the troops.

Meanwhile the Chipulina family was still in the Atlantic Hotel when Madeira experienced an earthquake. Despite the island's volcanic origins, earthquakes were by no means common. In fact this was the only one they experienced during their time there. I can remember sitting in the dining room of the hotel with my mother having lunch when it happened. The sensation was that of a very heavy lorry passing by and was in fact mistaken as such by both of us until all was revealed later that evening.

Soon after, the family moved to a small pension called Pensao Boavista in Rua Carreira. Boavista was something of a misnomer, but it was comfortable, very close to the centre of town, and within walking distance of the school. It was also quite close to the Headquarters of the 'Policia para Vigilança e Defensa do Estado', the PVDE. It was said that when the police band was practising in the patio it meant that some poor fellow was getting a hiding in the cells.

The food at the Pensao, which was dull but adequate, was occasionally supplemented by Lina with 'goodies' from a German Jewish delicatessen called Bach Irmaos which stood at the street corner. Their liver sausage was a particularly delicious item. Sunday treats included cakes from an Italian Patisserie at the other corner of the street followed by a film at the Teatro Municipal.

Teatro Municipal Madeira

In the early days most people were wary of buying cakes from the Patisserie because of its Italian connections. However, as soon as it was realised that Lady Liddell had no such qualms, all inhibitions were abandoned. Which is just as well as their cakes were superb.

For sheer artistry, however, one would have to turn to the confectionery sold by O Preto. His name was Portuguese for 'the blackman' and it was said that he was originally from either Angola or Moçambique. He was indeed a man of uncompromising blackness, something which he emphasised by always wearing a spotless white cap and equally spotless white clothes. The large flat baskets in which he carried his goodies were, of course, always delicately covered with a white cloth. Not that he stood about in street corners peddling his wares. Nothing so vulgar for O Preto. He took the stuff to hotels and private houses where he knew his bait was irresistible. The generally small pieces of glazed egg yolks, dates, flans, coconuts, chocolates and marzipans that he offered were a slimmer's nightmare and the flash of colour when he uncovered the basket was a treat in itself. But in fact he was not himself the artist. The goodies were actually the work of his two sisters.

1943 The owner of the pension was a decent man who lent Eric a wireless set so that he could keep track of the events of the war. He made good use of it, tuning in not just to the BBC, but also to the Voice of America which had a very powerful transmitter. The words which introduced the news from Portugal were also heard so frequently that they would remain not just in Eric's, but in the family's collective memory for years to come.

'Aqui Emissora Nacional, com Porto, Coimbra e Faro, em ondas courtas de 47 metros. '

For sheer artistry, however, one would have to turn to the confectionery sold by O Preto. His name was Portuguese for 'the blackman' and it was said that he was originally from either Angola or Moçambique. He was indeed a man of uncompromising blackness, something which he emphasised by always wearing a spotless white cap and equally spotless white clothes. The large flat baskets in which he carried his goodies were, of course, always delicately covered with a white cloth. Not that he stood about in street corners peddling his wares. Nothing so vulgar for O Preto. He took the stuff to hotels and private houses where he knew his bait was irresistible. The generally small pieces of glazed egg yolks, dates, flans, coconuts, chocolates and marzipans that he offered were a slimmer's nightmare and the flash of colour when he uncovered the basket was a treat in itself. But in fact he was not himself the artist. The goodies were actually the work of his two sisters.

1943 The owner of the pension was a decent man who lent Eric a wireless set so that he could keep track of the events of the war. He made good use of it, tuning in not just to the BBC, but also to the Voice of America which had a very powerful transmitter. The words which introduced the news from Portugal were also heard so frequently that they would remain not just in Eric's, but in the family's collective memory for years to come.

'Aqui Emissora Nacional, com Porto, Coimbra e Faro, em ondas courtas de 47 metros. '

June 1943 magazine of Emissora Nacional.

Never one to do things by halves, Eric would also often consult maps, as some of the places mentioned in the war news, particularly in the Russian front, were not exactly house-hold names.

During their stay at the pension Baba, who had by now passed her GCE examinations, left school and applied for work at the Consulate as well as for a teaching job at the British School. These were the only two places in which Gibraltarians were allowed to work by the Portuguese authorities. She got the latter and became a teacher. Her first salary was the equivalent of six pounds a month. She also undertook typing letters as the local censorship now required all letters to be typed. It was difficult to understand why there was any censorship at all. Apart from the A.A. batteries there was hardly a military secret to reveal in the whole archipelago.

One way or the other, Baba had become the breadwinner of the family. Although Eric had now finished school he was unable to get a job in Madeira. It was one of the conditions laid down by the evacuation authorities. Having little to do he spent most of his time at the Gibraltar Club playing cards with friends in a similar situation. He taught himself to touch-type and made extensive use of a nearby lending library which had a substantial selection of English language books. Generally it could be said that he lived the life of a penniless Lord.

During their stay at the pension Baba, who had by now passed her GCE examinations, left school and applied for work at the Consulate as well as for a teaching job at the British School. These were the only two places in which Gibraltarians were allowed to work by the Portuguese authorities. She got the latter and became a teacher. Her first salary was the equivalent of six pounds a month. She also undertook typing letters as the local censorship now required all letters to be typed. It was difficult to understand why there was any censorship at all. Apart from the A.A. batteries there was hardly a military secret to reveal in the whole archipelago.

One way or the other, Baba had become the breadwinner of the family. Although Eric had now finished school he was unable to get a job in Madeira. It was one of the conditions laid down by the evacuation authorities. Having little to do he spent most of his time at the Gibraltar Club playing cards with friends in a similar situation. He taught himself to touch-type and made extensive use of a nearby lending library which had a substantial selection of English language books. Generally it could be said that he lived the life of a penniless Lord.

My brother Eric, The penniless Lord.

Meanwhile blissfully unaware of hard times ahead, I continued to play my own innocent games. One day that summer, perhaps with little else to do, he took to pestering his mother for something or other. As she was busy with something else she tried to get rid of him by postponing his demands. 'I'll give it to you when it rains,' she said spontaneously.

It was a worthwhile ploy as it never rained in Madeira during the summer months. But this was the exception. Very shortly afterwards there was a freak storm and rain it did. The other members of the family began to revise their opinions of my psychic powers.

It was a worthwhile ploy as it never rained in Madeira during the summer months. But this was the exception. Very shortly afterwards there was a freak storm and rain it did. The other members of the family began to revise their opinions of my psychic powers.

1944 Back home Lieutenant-General Sir T. Ralph Eastwood became Governor.

Lieutenant-General Sir Ralph Eastwood. This photo was probably taken in 1945. The Governor is on the left. He is welcoming home repatriating Gibraltarians.

The risk of invasion had now all but disappeared and on the 28th of May the first official repatriation party left Madeira aboard the Indrapoera. The Chipulina family still had a year to wait. The first repatriation coincided with one of the most bizarre incidents to occur during the Second World War; the appearance on the Rock of General Montgomery's double, in a deception plan instigated to mislead the Germans as to the location and timing of the Normandy landings. Gibraltar was chosen as the ideal spot to show off the 'General' as it was almost certain his presence would be noted by the enemy. It was also the logical staging post for the General to use if he was planning a Mediterranean operation. The double was Lieutenant Clifton James, and the episode was re-lived in the 1958 film, 'I was Monty's Double.' James played both himself and Monty.

Clifton James on the right and the real thing on the left. Many Gibraltarians appeared as extras when the film was made in 1958 and most of my close friends took part. For some reason I missed all the fun and my Hollywood career never took off.

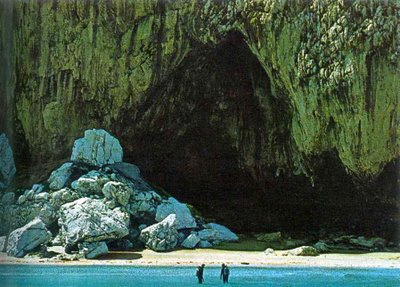

Meanwhile the military continued to blast and tunnel their way through the Rock. One of their operations led to the discovery of Gorham's cave on the Eastern cliff face, just round the corner from Sandy Bay.

A relatively recent photograph of Gorham’s cave. I have never understood why it took so long to discover. Its entrance is large enough and I remember being well aware if it when I used to go to Sandy Bay.

On the 6th of June D-Day began. After the Normandy landings the war was really over for Gibraltar. The bulk of the exiles from Tangier and Madeira began to return. The Londoners whose empty houses, flats and hotels had been requisitioned for the Gibraltarians now wanted their homes back. The exiles, however, were not returned to Gibraltar. They were moved to disused army huts on the outskirts of Belfast. There was still some time to go before they saw their beloved 'Piedra Gorda' once again.